All literature enchants and delights us, recovers us from the 10,000 things that distract us. The unenchanted life is not worth living.

31 July 2022

Hailing Frequencies Closed -- Nichelle Nichols (1932-2022)

06 July 2022

Somme Starlight

This year on Tolkien Reading Day I discussed the well-known tale of the inception of J. R. R. Tolkien's Middle-earth in a couple of lines he read the Old English poem Crist in 1913, which refer to the morning-star as Earendel. Convinced that there was a lost story behind that name, in 1914 he showed his close friend Geoffrey Bache Smith a poem he had written about Earendel. When Smith asked him what it all meant, Tolkien declared he would try to find out.

Over the course of decades Tolkien thought and wrote more about Earendel, although he never fully told his whole story. For so important a figure in his mythology to be most conspicuous by his absence is frustrating, but Verlyn Flieger has recently suggested that Tolkien may have left this story an 'untold tale' on purpose. In time he reshaped the name into Eärendil, 'the looked for that cometh at unawares, the longed for that cometh beyond hope! Hail Eärendil, bearer of light before the Sun and Moon! Splendour of the Children of Earth, star in the darkness, jewel in the sunset, radiant in the morning!' (S 248-49). When he sailed his ship, Vingilot, into the sky, wearing the silmaril bound upon his brow, it shone as a star of hope for the Elves and Men of a Middle-earth devasted by a hopeless war against Morgoth. Even Maedhros and Maglor, the bloody-handed, last remaining sons of Fëanor, were moved when they saw it.

Now when first Vingilot was set to sail in the seas of heaven, it rose unlocked for, glittering and bright; and the people of Middle-earth beheld it from afar and wondered, and they took it for a sign, and called it Gil-Estel, the Star of High Hope. And when this new star was seen at evening, Maedhros spoke to Maglor his brother, and he said: 'Surely that is a Silmaril that shines now in the West?'

(S 250)

Seven thousand years later in another war without hope, Sam Gamgee raised his eyes above the wastes of Mordor:

There, peeping among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high up in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and hope returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end the Shadow was only a small and passing thing: there was light and high beauty for ever beyond its reach.

(RK 6.ii.922)

Before continuing with Tolkien, let's take a moment to consider a quote which does not come from Tolkien at all, but from John Buchan's The Battle of the Somme (1916), a battle which he covered as a correspondent for The Times, while simultaneously holding an appointment at Wellington House, more transparently described as the British War Propaganda Bureau. Buchan, to be fair, does seem to have had a genuine interest in producing a work of History rather than a mere sham to be foisted on the British people. In this quote Buchan is not speaking in his own voice, but passing on the words of a witness whom he never identifies. He is describing the early morning hours of 14 July 1916:

“It was a thick night, the sky veiled in clouds, mottled and hurrying clouds, through which only one planet shone serene and steadily high up in the eastern sky. But the wonderful and appalling thing was the belt of flame which fringed a great arc of the horizon before us. It was not, of course, a steady flame, but it was one which never went out, rising and falling, flashing and flickering, half dimmed with its own smoke, against which the stabs and jets of fire from the bursting shells flared out intensely white or dully orange. Out of it all, now here, now there, rose like fountains the great balls of star shells and signal lights—theirs or ours—white and crimson and green. The noise of the shells was terrific, and when the guns near us spoke, not only the air but the earth beneath us shook. All the while, too, overhead, amid all the clamour and shock, in the darkness and no less as night paled to day, the larks sang. Only now and again would the song be audible, but whenever there was an interval between the roaring of the nearer guns, above all the distant tumult, it came down clear and very beautiful by contrast, Nor was the lark the only bird that was awake, for close by us, somewhere in the dark, a quail kept, constantly urging us—or the guns—to be Quick-be-quick.”

(p. 33 Kindle edition)

The framing of this quote is marvelous. It begins with the planet shining high and steady and serene and ends with the beauty of larks' who sang above the trenches in the dawn (a constant of the poetry of this war) while the artillery barrage flashed and thundered, but who were heard only in the silent moments between detonations. In the planet and the larks, we see something of the remoteness of the beauty above the 'forsaken land' which we also find in Tolkien's accounts of Sam and Maglor and Maedhros gazing up at that same white star seven millennia distant from each other, but equally gazing up at it without hope until they see it. Fëanor's sons eschew a hope they recognize for a tragedy they have helped stage, being unable to let go of the hold their oath has on them; Sam takes the lesson of the selflessness of hope from the selfishness of his defiance. Like Maedhros and Maglor, however, the speaker of this quote finds the situation on the ground more complicated and less clear. The quail, sharing the darkness and the earth with the men in the trenches, call ambiguously. Are they encouraging the guns to be quick and done, or the soldiers to be quick rather than dead?

That planet, though. Shining high in the East before dawn in mid-July of 1916, it could be Jupiter or Venus. According to an astronomical almanac I found for 1916, Jupiter would have risen about 11:40 PM on 13 July, followed by Venus at roughly 3:30 AM on 14 July, and the sun at 4:13 AM. So Jupiter would have been much higher in the sky before dawn than Venus, though Venus would have been much brighter. So, I would guess that the planet Buchan's source was looking at was Jupiter. But Buchan's anonymous source was not the only British soldier who might have gazed up at the sky from the battlefields of the Somme. Buchan also tells us that the last week of July and the first fortnight of August had 'blazing summer weather', which he contrasts with the 'rain and fog' of the third week of July. Together with a remark about the heat on men wearing steel helmets, this gives us a picture of a hot sun beating down out of a clear sky (p. 38 Kindle edition). Again according to that almanac, Venus rose earlier and grew brighter each morning, peaking at a stunning apparent magnitude of -4.7 in early August. In technical terms that's really-damn-bright™.

Perhaps on one of those early mornings or towards the end of a duty shift at night, Tolkien looked up from the forsaken land of the Somme, and the high beauty of the morning star -- Venus, Earendel, Eärendil, call it what you will -- smote his heart and hope returned for a while. It's hard to believe he didn't see it, and that seeing it he wouldn't have thought of the lines from Crist with which his quest for Eärendil began. My incredulity proves nothing, of course. Yet Tolkien would have needed any glimpse of hope he could get during these weeks especially. For around 16 July he learned from Geoffrey Bache Smith that their other close TCBS friend, Christopher Quilter Gilson, who was also at the Somme, had been killed on the battle's first day. Perhaps, too, years later he remembered seeing the morning star above the Somme and wrote it into Maedhros and Maglor, but especially into Sam.

Given the horrors of the battlefield and the loss of so beloved a friend, Tolkien might not have seen hope in the beauty of the morning star. It may well have been far too soon for hope, at least for himself. After all neither Maedhros and Maglor nor Sam take the sight of the morning star as a sign of hope for themselves, that they would succeed or survive, but only for the world at large.

His song in the Tower had been defiance rather than hope; for then he was thinking of himself. Now, for a moment, his own fate, and even his master’s, ceased to trouble him. He crawled back into the brambles and laid himself by Frodo’s side, and putting away all fear he cast himself into a deep untroubled sleep.

(RK 6.ii.922)

'I went out into the wood – we are out in camp again from our second bout of trenches still in the same old area as when I saw you – last night and also the night before and sat and thought.'

Tolkien replying on 12 August 1916 to Geoffrey Bache Smith's letter about Christopher Quilter Gilson's death. (Letters #5, p. 9).

30 June 2022

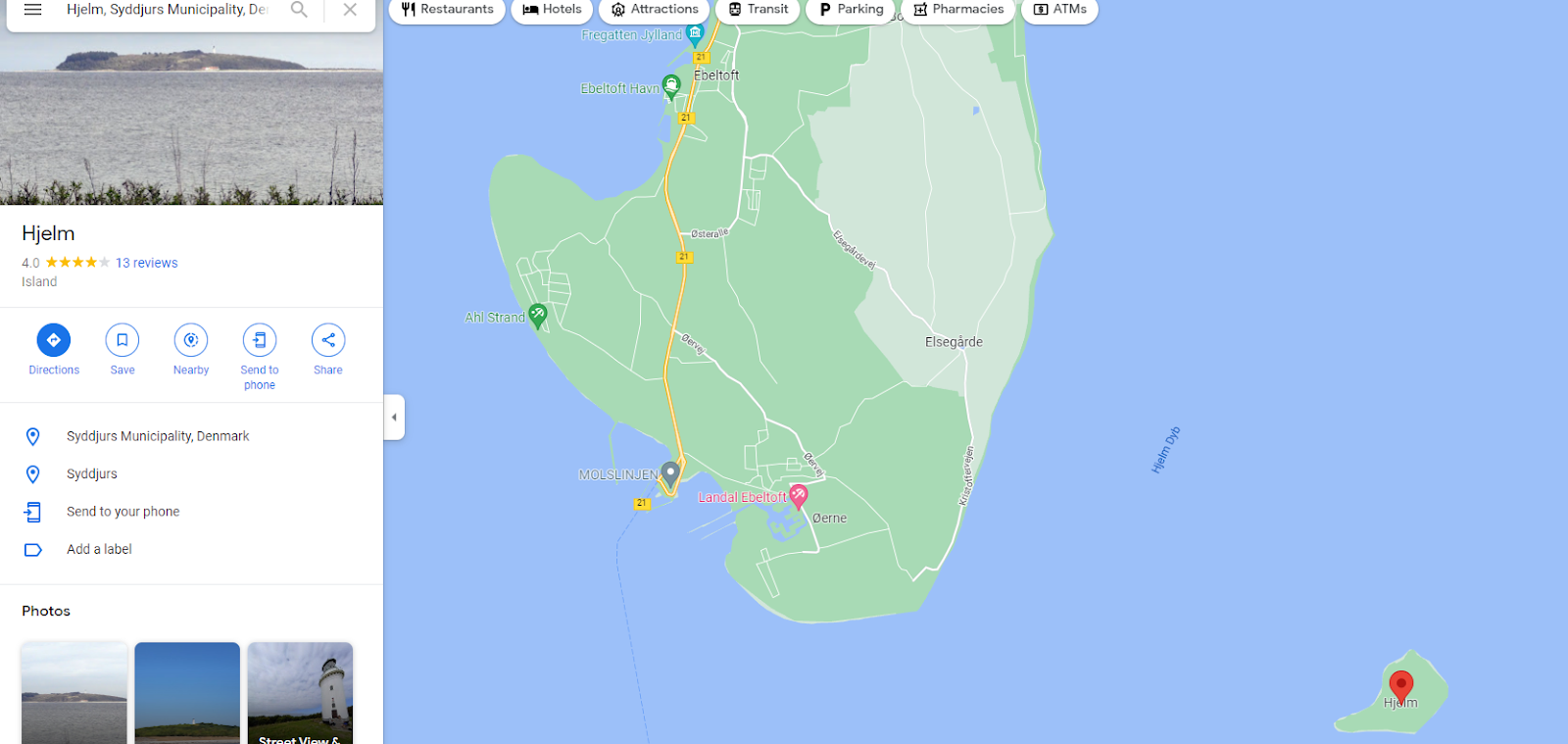

Hjelm Dyb and Helm's Deep

|

| Hjelm Island from Hjelm Dyb, photo courtesy of Dr. B. A. Kaiser |

- "the great stones of it were set with such skill that no foothold could be found at their joints, and at the top they hung over like a sea-delved cliff" (TT 3.vii.533);

- "But the Hornburg still held fast, like an island in the sea" (TT 3.vii.536).

- "They wavered, broke, and fled back; and then charged again, broke and charged again; and each time, like the incoming sea, they halted at a higher point" (TT 3.vii.533).

- "Against the Deeping Wall the hosts of Isengard roared like a sea" (TT 3.vii.535).

- "Over the wall and under the wall the last assault came sweeping like a dark wave upon a hill of sand."

28 June 2022

Hope Shall Come Again: 'The Choices of Master Samwise' and 'The Children of Húrin'

He looked on the bright point of the sword. He thought of the places behind where there was a black brink and an empty fall into nothingness. There was no escape that way. That was to do nothing, not even to grieve.(TT 4.x.732)

How many can I kill before they get me? They’ll see the flame of the sword, as soon as I draw it, and they’ll get me sooner or later. I wonder if any song will ever mention it: How Samwise fell in the High Pass and made a wall of bodies round his master. No, no song. Of course not, for the Ring’ll be found, and there’ll be no more songs.(TT 4.x.735)

At least I would say that Tragedy is the true form of Drama, its highest function; but the opposite is true of Fairy-story. Since we do not appear to possess a word that expresses this opposite—I will call it Eucatastrophe. The eucatastrophic tale is the true form of fairy-tale, and its highest function.(OFS ¶ 99)

And if the catastrophe that marks a Tragedy cleanses us or purges us by means of fear and pity, then we can see the parallel between Drama and Fairy-stories even more clearly. For the eucatastrophe that is the 'true form' and 'highest function' of a fairy tale cleanses us through Escape, Recovery, and Consolation. It includes the renewed clarity of 'vision' we gain through Recovery (OFS ¶ 83-84). but goes beyond it by allowing a 'vision' of a transcendent reality (OFS ¶ 103).

There is more to be explored here, which I don't have time for right now. For example, an essential aspect of the situation Sam finds himself in here is the battle he has with Shelob directly before he comes to believe Frodo dead. For the narrator there names both Beren, the fairy-tale hero who also fought giant spiderlike monsters, and Túrin, the tragic hero who slew a dragon by stabbing him from below only to learn terrible truths about his own life in doing so. Sam of course is neither of these great heroes, sons of the chieftains of their peoples, and further reflection on these passages may well help us more deeply understanding of On Fairy-stories, The Lord of the Rings, and how the dynamic balance of Tragedy and Eucatastrophe fundamentally shapes Tolkien's Secondary World.

___________________________

If anybody knows of another discussion of these particular allusions to The Children of Húrin in The Choices of Master Samwise, please do let me know. I would be eager to see it.

23 April 2022

Fear in a handful of dust: reflections in Frodo's dusty mirror (FR 1.iii.68)

‘I shall get myself a bit into training, too,’ he said, looking at himself in a dusty mirror in the half-empty hall. He had not done any strenuous walking for a long time, and the reflection looked rather flabby, he thought.

(FR 1.iii.68)

Anton Chekhov famously advised younger writers that the details they introduce early in their works are not to be taken lightly. A loaded gun onstage in the first act must be used before the end. We call this Chekhov's Gun. That he also famously broke his own rule in The Cherry Orchard need not detract from lesson. For he did not break his rule lightly. Donald Rayfield has noted that the failure of the gun to go off in The Cherry Orchard reflects the thematic failure of the characters to do anything.* Great writers are masters of the rules, even their own.

The detail of course need not be a loaded gun. It can just as well be a mirror. If an author calls attention to a mirror, whether actual or enchanted, the reader should pay attention. We would naturally expect more from an enchanted mirror. In Harry Potter, for example, the Mirror of Erised reveals the greatest desire of those who look into it, which tells a great deal about their character. The Mirror of Galadriel is more challenging, with its visions of past, present, and future, and who knows which is which and who is who; and as with all things prophetic, sometimes the visions glimpsed come true only because the one who sees them tries to stop them.

Whether ordinary or enchanted, however, mirrors in stories present not only reflections of, but reflections on, those who look into them. Naturals mirrors, bodies of clear, still water can also reveal whether we are a Narcissus or Durin when we look into them. Windows, too, can open onto new sights or old sights made as new, as when Frodo has his blindfold removed in Lothlórien:

The others cast themselves down upon the fragrant grass, but Frodo stood awhile still lost in wonder. It seemed to him that he had stepped through a high window that looked on a vanished world. A light was upon it for which his language had no name. All that he saw was shapely, but the shapes seemed at once clear cut, as if they had been first conceived and drawn at the uncovering of his eyes, and ancient as if they had endured for ever. He saw no colour but those he knew, gold and white and blue and green, but they were fresh and poignant, as if he had at that moment first perceived them and made for them names new and wonderful. In winter here no heart could mourn for summer or for spring. No blemish or sickness or deformity could be seen in anything that grew upon the earth. On the land of Lórien there was no stain.

(FR 2.vi.350)

With 'no stain', no blindfold, with nothing to come between the one perceiving and the thing perceived we see a different world. Tolkien spoke of this 'clear view' of the world and its importance in his essay On Fairy-stories:

Recovery (which includes return and renewal of health) is a re-gaining—regaining of a clear view. I do not say “seeing things as they are” and involve myself with the philosophers, though I might venture to say “seeing things as we are (or were) meant to see them”—as things apart from ourselves. We need, in any case, to clean our windows; so that the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of triteness or familiarity—from possessiveness. Of all faces those of our familiares are the ones both most difficult to play fantastic tricks with, and most difficult really to see with fresh attention, perceiving their likeness and unlikeness: that they are faces, and yet unique faces. This triteness is really the penalty of “appropriation”: the things that are trite, or (in a bad sense) familiar, are the things that we have appropriated, legally or mentally. We say we know them. They have become like the things which once attracted us by their glitter, or their colour, or their shape, and we laid hands on them, and then locked them in our hoard, acquired them, and acquiring ceased to look at them.

(OFS ¶ 83)

So when we see the mirror in the hall at Bag End and it is dusty, both the mirror and the dust upon it are details we should not take lightly. Frodo's grimy mirror is as much a signal as Chekhov's Gun. The dust on the mirror, moreover, is more problematic than dirt on a window. For it affects the light reflected twice, both before and after it reaches the mirror. The image is thus distorted in its creation and in its perception. The dust here invites us to note more than that Frodo is less fastidious housekeeper than his uncle was. (But, really, what would Bilbo say?). So what is Frodo not seeing as he was meant to see it?

He notices he's carrying some extra weight around his middle, which given his age is nothing unusual. Nor is it surprising that he looks forward to walking some of those pounds off on the journey he is about to set out on. What he is not seeing is something that his neighbors clearly have noted despite the weight he's put on, namely, that at fifty he looks the same as he had seventeen years earlier when Bilbo left, like 'a robust and energetic hobbit just out of his tweens'. He was showing the same 'queer' 'preservation' which Bilbo had shown (FR1.ii.42-43). He knows all about this particular effect of the Ring. He also knows that he must leave the Shire in order to save it and get rid of the Ring. That is the entire point of the journey he is about to embark on. Yet when he looks in the mirror, he does not even notice how young he looks, let alone make a connection between his youthful appearance and its 'preservation' by the Ring.

The next time he looks in a mirror, in Rivendell, he will at last pick up on how young he looks as well as how much thinner he looks:

Looking in a mirror he was startled to see a much thinner reflection of himself than he remembered: it looked remarkably like the young nephew of Bilbo who used to go tramping with his uncle in the Shire; but the eyes looked out at him thoughtfully. ‘Yes, you have seen a thing or two since you last peeped out of a looking-glass,’ he said to his reflection. ‘But now for a merry meeting!’ He stretched out his arms and whistled a tune.

(FR 2.i.225)

Although Aragorn had rebuked him for joking about becoming so thin that he would turn into a wraith (FR 1.xi.184), he still sees only a little more than he had when he looked in the mirror at Bag End. Although he has in fact only just barely escaped being turned into a wraith by the Nazgûl, Frodo still makes no connection between his appearance and the Ring. He is surprised and, I think, clearly pleased by his young, trim appearance. Yet there is also a distance between him and the reflection. 'It' does not look like him, but like 'the young nephew of Bilbo', and it is not 'his eyes' that look out at him, but 'the eyes.' He addresses 'it' in the second-person, as people sometime do, but, while he whistles a tune and anticipates an evening of mirth, he leaves the eyes and their thoughtful look behind. By contrast in Bag End, he had looked at 'himself' in the glass, and not a 'reflection of himself', and had spoken to himself in the first-person as he did so. Even if he now sees the remarkable preservation which he did not see before, his identification with the reflection is less.

Considering what else Frodo and others see and how they see it on this Frodo's first day conscious in Rivendell will help us understand his interactions with his reflections. In Gandalf's conversation with Frodo that morning the complexities of perceiving the world and those in it accurately come to the fore several times. These range from simple matters of misperception based on misconceptions -- such as the moral and intellectual qualities of Men or the truth about Strider and the Rangers -- to more recondite questions of the horizons of mundane reality -- the visibility of the Black Riders to Frodo and the light shining from Glorfindel, whose worlds overlap with, but are not perceptually the same as, the everyday world.

Near the end of their conversation Gandalf 'took a good look at Frodo': 'there seemed to be little wrong with him. But to the wizard's eye there was a faint change, just a hint as it were of transparency....' Yet the subtle eye of Gandalf is uncertain what to make of this 'transparency.' He concedes that such transparency is not unexpected. In addition to the grave wound inflicted on him by the Morgul knife, which was causing him to fade into the world of the Ringwraiths (FR 2.i.219, 222), Frodo is a mortal who possesses a Ring of Power and has used it more than once to become invisible. One of the first lessons Gandalf tried to impart to Frodo was that mortals who use such rings fade (FR 1.ii.47).

As a result, Gandalf found himself not quite certain what the hobbit would come to in the end. While he expected that Frodo would not come 'to evil', he qualified that notion with 'I think', followed by the concession that not even Elrond could 'foretell' what would become of Frodo. (And foretelling presupposes foreseeing.) His final thought, that Frodo 'may become like a glass filled with clear light for eyes to see that can' sounds much more hopeful, and it is, but it must nevertheless be read in the context of Gandalf's just expressed uncertainties, which his use of 'may become' shows to be unresolved because the future he hoped for is unrealized so far. If Frodo is filled with light now, Gandalf doesn't seem to see it -- even if Sam apparently can (TT 4.iv.651-52). The wizard's immediate pronouncement to Frodo -- 'you look splendid' -- further emphasizes his private reservations by disassociating them from his outward certainties.

That same evening Frodo's unexpected 'merry meeting' with Bilbo takes a very dark turn when Bilbo asks to see the Ring and then reaches out to touch it. As he does so, Frodo suddenly sees Bilbo as through 'a shadow', and his beloved uncle appears to him to be a Gollum-like creature whom he wished to strike. What Bilbo sees in Frodo's face at this moment is never described, but it was clearly more than a thoughtful look in his eyes. His reaction makes plain that what he saw reflected in Frodo's face brought home to him an understanding of the Ring which years of badgering by Gandalf and his own nearly violent clash with Gandalf the night he left Bag End had been unable to accomplish.

Bilbo looked quickly at Frodo’s face and passed his hand across his eyes. ‘I understand now,’ he said. ‘Put it away! I am sorry: sorry you have come in for this burden; sorry about everything. Don’t adventures ever have an end? I suppose not. Someone else always has to carry on the story. Well, it can’t be helped. I wonder if it’s any good trying to finish my book? But don’t let’s worry about it now – let’s have some real News! Tell me all about the Shire!’

(FR 2.i.232)

We see a very different Bilbo here than the one who argued fiercely with Gandalf about the Ring back in the Shire. That Bilbo had laid his hand on the hilt of his sword when Gandalf insisted he leave the Ring behind. That Bilbo, even after he backed down and let go of his sword, tried to suggest that Gandalf was the problem (FR 1.i.34): 'I don't know what has come over you, Gandalf'. This Bilbo passes his hand in front of his eyes, as if to wipe away what he has seen, and backs down, not because he has been intimidated, but because he understands. He says he is sorry three times, and in this moment at last sees the matter of the Ring as a burden, which only a minute earlier he had made light of: 'Fancy that ring of mine causing such a disturbance!' (FR 2.i.232). His reaction here has far more in common with the 'sudden understanding' and the pity he felt for Gollum beneath the Misty Mountains long ago. True Hobbit that he is, Bilbo then deflects the burden of the moment with levity and an appeal for all the gossip from home, thus converting this sharp instant back into the sort of a 'merry meeting' Frodo had looked forward to as he walked whistling away from the looking-glass in which he could not quite see as clearly as Bilbo just has.

The dust on the mirror at Bag End, obscuring Frodo's image of himself and skewing his perception is the metaphorical herald of the shadow that falls between him and Bilbo here. He's looked through this shadow before, however, as we can see in The Flight to the Ford, when he was fading because of the wound inflicted at Weathertop. It obscured the faces of his friends during the day and by the night it made the world seem 'less pale and empty' (FR 1.xii.210, 211). Yet metaphorical or not, it still obscures his view and hints at the influence the Ring already has over him, much like his inability to throw the Ring even into a fire that he knew could not harm it and his reluctance to let Gandalf touch it.

But it is more than this. For, at the far end of this spectrum of occlusion, we find the Eye of Sauron looking at Frodo out of the last mirror he looks into, and the Eye also cannot see what it is searching for, cannot descry what it is most important to it without a blunder by the Ring-bearer, cannot read the hearts of others, because for all its watchfulness it is covered in the glaze of its own possessiveness and measures all other things by its own desires. It is framed by and filled with emptiness.

But suddenly the Mirror went altogether dark, as dark as if a hole had opened in the world of sight, and Frodo looked into emptiness. In the black abyss there appeared a single Eye that slowly grew, until it filled nearly all the Mirror. So terrible was it that Frodo stood rooted, unable to cry out or to withdraw his gaze. The Eye was rimmed with fire, but was itself glazed, yellow as a cat’s, watchful and intent, and the black slit of its pupil opened on a pit, a window into nothing.

(FR 2.vii.364, italics added)

After the crisis passes in Bilbo's argument with Gandalf about the Ring, Bilbo also passed his hand over his eyes as if clearing something from his vision, and spoke of the feeling that the Ring was an eye looking at him. He wanted just to put it on and disappear. In reply Gandalf tells him to 'stop possessing it' (FR 1.i.33). Such possessiveness gave the Ring 'far too much hold on you. Let it go! And then you can go yourself, and be free.' (FR 1.i.33). And it is of course in giving it up that he became as free of the Ring as he ever could be.

Possessiveness, Tolkien tells us in the passage of On Fairy-stories quoted above, keeps us from seeing things 'as we are (or were) meant to see them'. As he says, we find things attractive because of 'their glitter, or their colour, or their shape', things we then appropriate and possess like a dragon brooding upon their hoard, things we then stop looking at because the possession has become what matters. Recall how Frodo looks at the Ring:

It now appeared plain and smooth, without mark or device that he could see. The gold looked very fair and pure, and Frodo thought how rich and beautiful was its colour, how perfect was its roundness. It was an admirable thing and altogether precious.

(FR 1.ii.60)

Or how Déagol 'gloated over' it, if ever so briefly:

And behold! when he washed the mud away, there in his hand lay a beautiful golden ring; and it shone and glittered in the sun, so that his heart was glad.

(FR 1.ii.52)

An ordinary person who has 'appropriated' and 'possessed' an ordinary thing in the sense Tolkien means these words in On Fairy-stories would need to experience the Recovery of a 'clear view' which fairy stories offer before he can see that thing 'as we are (or were) meant to see them.' Even so, to shake a person free of such possessiveness might take some doing, or so Tolkien's likening the possessor to a dragon sitting on a hoard suggests. Viewing these passages alongside the description of possessiveness in On Fairy-stories, I think we can safely say that we see as we were meant to see them, and perhaps even as they really are. Possessiveness may not blind the possessor (though it very well might), but it obscures their view, whether we think of it metaphorically as dust on the mirror, dirt on a window, or a shadow between familiar faces which we find we no longer know.

The power of the Ring complicates matters, however. Its color, shape, glitter, and beauty are a small part of its allure, yet it is not 'so small a thing' as Boromir calls it when about to succumb to its pull (FR 2.x.397-98). To speak more precisely, the power inherent in the Ring captures its possessor, just as the gravity of a more massive body captures a less massive body. The possessor is possessed in turn, and so enslaved, and so devoured. The possessiveness powered by the Ring does 'play fantastic tricks' with the faces of our familiares and sets them friends against each other. Frodo sees not just Bilbo as a Gollum-like creature, but Sam as an Orc (RK 6.i.911-12; cf. 6.iii.936). Sméagol murders Déagol; Bilbo threatens Gandalf with a sword; Frodo does the same to Sam. The thirty-three year old face fifty year old Frodo sees in the mirror should be both familiar and not startlingly, not remarkably, but disturbingly strange. He should see its 'likeness and unlikeness' to the face he knows as that of Frodo Baggins. He should know it isn't right, but the dust and shadows of the possessiveness that comes with the Ring prevents him from having a 'clear view.'

As Gandalf thought when he looked at Frodo that morning at Rivendell, 'he is not half through yet.' By the time he is all the way through, he will be more in need of Recovery, of the clear view, the fairy tale can bring. But as Frodo learns tales don't always end well for those inside them. Whatever glimpse of joy the eucatastrophe of Mount Doom may bring the reader, it brings Frodo consolation for the loss of the thing that possessed him. He must leave the tale, and seek his Recovery elsewhere, where 'the grey rain-curtain turned all to silver glass and was rolled back, and he beheld white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise' (RK 6.ix.1020).

_______________________________

* The wikipedia article on Chekhov's Gun quotes three examples of Chekhov giving this advice, and provides the citations for The Cherry Orchard and the work of Donald Rayfield. I will confirm these citations at the first opportunity.

Star Trek: Picard offers us a splendid example of Chekhov's Gun. In the fourth episode of the second season a gun hangs above the mantel in Chateau Picard and in the fifth episode one of the characters uses it. Extra points here since this also counts as an allusion of Pavel Chekov of Star Trek: The Original Series.

QED: 'I will show you fear in a handful of dust.'