Recently I saw someone somewhere inline asking about Gandalf's characterization of Gollum in The Shadow of the Past.

The most inquisitive and curious-minded of that family was called Sméagol. He was interested in roots and beginnings; he dived into deep pools; he burrowed under trees and growing plants; he tunnelled into green mounds; and he ceased to look up at the hill-tops, or the leaves on trees, or the flowers opening in the air: his head and his eyes were downward.

(FR 1.ii.53)

The poster wanted to know what was so wrong about his not looking up but down. The characterization starts off well enough, but it begins to feel like something has gone wrong when it reaches "and he ceased ... air." And the last phrase, singled out and pointed to by the colon, reads like a final verdict in a capital case. So why is downward bad?

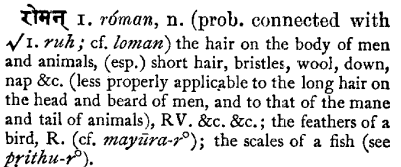

It's part of an old notion that looking up, whether to the heavens or to heaven, is something that distinguishes humans from animals. Off the top of my head I am unsure where it started, but it can be found in Plato and Aristotle. Tolkien was certainly familiar with Plato's Timaeus, which along with the Critias, speaks of Atlantis, and helped inspire Númenor. The description from The Shadow of the Past quoted above makes me think that Tolkien would have more likely been drawing on Boethius' The Consolation of Philosophy, an exceptionally important work in the Middle Ages in Europe. There is even a translation of it into Old English, which has been attributed to Alfred the Great. It probably wasn't really translated by Alfred himself, however, and it's really more of a reboot than a straighforward translation. Tolkien certainly knew both of these works, each of which contains at a similar moment in its fifth book a poem on this difference between humans and animals. First take a look at my translation of a Latin poem from the fifth book of The Consolation of Philosophy. I include the original after that. I've also tried to keep the translation close to the original, line for line, more or less, if not word for word. It's not, however, a literal translation, and I have not tried putting it into verse.

Creatures of such different shapes wander the earth!

Some lie stretched in the dust and sweep it,

And propelled by the strength of their body

They drag a continuous furrow in the earth.

Others beat the air with their light wandering wings

And swim in liquid flight the vast spaces of the heavens.

Still others happily leave their footprints on the ground

Whether crossing green fields or entering a wood.

All these creatures, you see, differ in shape,

Yet their downward gaze can only weigh down their dull senses.

Mankind alone raises its lofty summit higher,

Stands erect and looks down on the earth as trivial.

Unless you have mud for brains, your human form bids

You raise up your soul also when with face uplifted

You seek the heavens, lest your mind, weighed down

And inferior, sink down when your body is raised higher.

Quam uariis terras animalia permeant figuris!

Namque alia extento sunt corpore pulueremque uerrunt

Continuumque trahunt ui pectoris incitata sulcum,

Sunt quibus alarum leuitas uaga uerberetque uentos

Et liquido longi spatia aetheris enatet uolatu,

Haec pressisse solo uestigia gressibusque gaudent

Vel uirides campos transmittere uel subire siluas.

Quae uariis uideas licet omnia discrepare formis,

Prona tamen facies hebetes ualet ingrauare sensus.

Vnica gens hominum celsum leuat altius cacumen

Atque leuis recto stat corpore despicitque terras.

Haec nisi terrenus male desipis, admonet figura,

Qui recto caelum uultu petis exserisque frontem,

In sublime feras animum quoque, ne grauata pessum

Inferior sidat mens corpore celsius leuato.

And now my translation of the Old English, followed by the original:

You might have noticed, if you enjoy such thoughts,

That many different creatures exist on the earth.

They have various colors and modes of movement

And forms of many kinds known and unknown.

Some creep and crawl, their whole body pressed to the earth;

they get no help from feathers, they cannot go on foot,

they cannot, as it is their fate, take pleasure in the earth.

Some others walk the earth on two feet,

some do so on four, some on beating wings

soar under heaven. Yet each of these creatures

inclines to the ground, bends its head down,

looks upon this world, wants from the earth

some necessity, some object of desire.

Man alone of God's creatures goes

with his face directed upwards.

By this it is betokened that his faith

and mind should look more up to heaven

than down, lest he turn his soul downward as a beast does.

It is not fitting that any man's mind

be bent downwards and his face upwards.

Hwæt ðu meaht ongitan, gif his ðe geman lyst,

Þætte mislice manega wuhta

geond eorðan farað ungelice.

Habbað blioh and fær bu ungelice

and mæg-wlitas manega cynna

cuð and uncuð. Creopað and snicað,

eall lichoma eorðan getenge;

nabbað hi æt fiðrum fultum, ne magon hi mid fotum gangan,

Eorð brucan, swa him eaden wæs.

Sume fotum twam foldan peððað,

Sume fierfete, sume fleogende

windað under wolcnum. Bið ðeah wuhta gehwylc

onhnigen to hrusan, hnipað ofdune,

on weoruld wliteð, wilnað to eorðan,

sume nedþearfe, sume neodfræce.

Man ana gæð metodes gesceafta

Mid his andwlitan up on gerihte.

Mid ðy is getacnod þæt his treowa sceal

and his modgeþonc ma up þonne niðer

habban to heofonum, þy læs he his hige wende

niðer swa ðær nyten. Nis þæt gedafenlic

þaet se modsefa monna æniges

niðerheald wese and þæt neb upweard.

So the problem with Gollum looking down all the time is that he has stopped being human and become an animal instead. This is analogous to something Boethius says earlier in The Consolation, that "the man who ceases to be human because he has abandoned goodness, turns into a beast since he cannot be transformed into a godlike state" (4.3). It's also worth remembering how Gollum is sometimes called "it" rather than "he," a "creature," a "thing," and is likened to an insect, a spider, and a dog. In fact, all of these words are used of him throughout The Taming of Sméagol. Fittingly, when Frodo and Sam first see Gollum in this chapter, he is "creeping" and "crawling" down the cliff-face head first, words which echo the sixth line in the Old English poem above: "creopað and snicað." I must admit, however, that I'm disappointed to find that "snicað" does not seem etymologically connected to "sneak." It would be so nice to hear Gollum's response to Sam's accusation of "sneaking" on the stairs: "snicð! snicð!" he hiscte."