In her splendid study, A Question of Time: J.R.R. Tolkien's Road to Faërie, Verlyn Flieger illuminates the role of time and dreams in The Lost Road, The Notion Club Papers, and The Lord of the Rings, all of which Tolkien worked on from the middle 1930s through the late 1940s, switching from one to another and back again, but always weaving and reweaving the web of his thoughts into a more complete portrait of time, dreams, and the realms of mortal and fairy. As Professor Flieger states:

[In The Lord of the Rings] dreams are not so much a part of the action as correlative to it. They correlate the waking and the sleeping worlds, they parallel or contrast conscious with unconscious experience, and they act as chronological markers. Free in a way the rest of the narrative is not to move beyond the confines of conscious experience, the dreams in The Lord of the Rings reach into unsuspected regions of the mind, bridge time and space, and so demonstrate the interrelationship between dreaming and waking that the two states can be seen as a greater whole.

(175-76)

So comprehensive is her account of Tolkien's thought and practice in this regard that it is hard to imagine any future work on this subject being taken seriously which does not take hers into account. There is one area, however, in which I think we might build upon and advance her analysis. Professor Flieger has likened the hobbits' time in the Old Forest and with Tom Bombadil to a dream, and suggested that here begins the waking dream or dreamlike state to which Frodo refers in Homeward Bound when he says that returning to the Shire feels like falling asleep again (Flieger, 198ff; RK 6.vii.997).

Now there are certainly dreams involved in the chapters where Bombadil appears, but other states of consciousness are also in play and just as widely visible. In fact, I would argue, the entire sequence from the time the hobbits enter the Old Forest until they reach Bree at the end of Fog on the Barrow-Downs marks a journey into Faërie, and our first extended encounter with the various states of consciousness which we will meet over and over again throughout The Lord of the Rings.

We have previously seen such states touched upon: as when we learn that Frodo has been troubled by dreams of late (

FR 1.ii.43); as when the moment with the thinking fox suggests a larger consciousness of and in the world than the hobbits know of (1.iii.72); as when Sam, Pippin, and Frodo meet Gildor and the Elves in the woods of the Shire (1.iii.79-85), and find themselves, respectively, "as if in a dream," "in a waking dream," and, owing to the enchanted properties of elvish minstrelsy, understanding and remembering songs sung in a language imperfectly known (1.iii.81, 82, 79). All of these passages prepare the ground for the sequence involving Old Man Willow, Tom Bombadil, and the Barrow Wight.

To these suggestions of a larger world of perception than either "normal consciousness" or "dreams" can describe we may add various indications that emphasize the physical boundaries put between themselves and "normal" life in the Shire. Consider Sam's thoughts as they escape across the river in the fog (1.v.99):

He had a strange feeling as the slow gurgling stream slipped by: his old life lay behind in the mists, dark adventure lay in front. He scratched his head, and for a moment had a passing wish that Mr. Frodo could have gone on living quietly at Bag End.

Note how the ephemerality of Sam's wish is doubly emphasized by 'for a moment' and 'passing.' It suits him. Only that morning he had declared his resolution to go only forward on this 'very long road into darkness' as well as his certainty that he has 'something to do before the end, and it lies ahead, not in the Shire' (1.iv.87). As if to make clear that a line has been crossed which cannot be recrossed, a Black Rider appears on the far bank behind them. Merry asks 'What in the Shire is that?' (1.v.99). How small their world has been till now.

The next morning the fog still shrouds them as they depart the Shire and enter the Old Forest by crossing a hedge (1.vi.109-110), which is as much a defensive wall against what is outside as a boundary for what is within. This is not the first time that crossing a hedge has marked a departure from an old life. When leaving Bag End, Bilbo 'jumped over a low place in the hedge at the bottom [of the path], and took to the meadows, passing into the night like a rustle of wind in the grass' (1.i.36). Seventeen years later, Frodo, together with Sam and Pippin, 'jumped over the low place in the hedge at the bottom and took to the fields, passing into the darkness like a rustle in the grasses' (1.iii.70). Surely the near identity of phrasing here is meant to draw a line under these two moments of transition, just like the words that mark their crossing the hedge which is the border of the only world they have ever known:

It was dark and damp. At the far end it was closed by a gate of thickset iron bars. Merry got down and unlocked the gate, and when they had all passed through he pushed it to again. It shut with a clang, and the lock clicked. The sound was ominous.

‘There!’ said Merry. ‘You have left the Shire, and are now outside, and on the edge of the Old Forest.’

(1.vi.110)

With their world now behind them Merry cautions them about the sentience and ill will of the trees (1.vi.110), which the hobbits before long feel oppressing them (1.vi.111-112). In an effort to 'encourage' his companions Frodo begins a song, but unlike the song of the elves which drove off the Black Rider (1.iii.78), his song has only power enough to provoke the trees further (1.vi.111). Soon the hobbits themselves fall victim to the more powerful song of Old Man Willow, which only Sam manages to recognize and resist (1.vi.116-17). This allows him to rescue Frodo, which leads to a telling exchange between them:

‘Do you know, Sam,’ he said at length, ‘the beastly tree threw me in! I felt it. The big root just twisted round and tipped me in!’

‘You were dreaming I expect, Mr. Frodo,’ said Sam. ‘You shouldn’t sit in such a place, if you feel sleepy.’

‘What about the others?’ Frodo asked. ‘I wonder what sort of dreams they are having.’

They went round to the other side of the tree, and then Sam understood the click that he had heard. Pippin had vanished. The crack by which he had laid himself had closed together, so that not a chink could be seen. Merry was trapped: another crack had closed about his waist; his legs lay outside, but the rest of him was inside a dark opening, the edges of which gripped like a pair of pincers.

(1.vi.117)

|

"Old Man Willow" © The Tolkien Estate

|

Despite Sam's suggestion that Frodo has been dreaming, the reader knows otherwise. The beastly tree has thrown him in, and Old Man Willow's swallowing of Merry and Pippin proves it. Whatever Sam may think just now, this is no dream, but a state of enchanted consciousness.

Unable to help his friends, Frodo runs about crying for help, and Tom Bombadil comes hopping and dancing down the path. When Sam and Frodo rush at him in desperation, he stops them dead with a word and a raised hand. With a song and a few (as always) rhythmic words he then turns the tables on Old Man Willow, forcing him to disgorge Merry and Pippin and sending him to sleep (1.vi.119-120).

‘What?’ shouted Tom Bombadil, leaping up in the air. ‘Old Man Willow? Naught worse than that, eh? That can soon be mended. I know the tune for him. Old grey Willow-man! I’ll freeze his marrow cold, if he don’t behave himself. I’ll sing his roots off. I’ll sing a wind up and blow leaf and branch away. Old Man Willow!’ Setting down his lilies carefully on the grass, he ran to the tree. There he saw Merry’s feet still sticking out – the rest had already been drawn further inside. Tom put his mouth to the crack and began singing into it in a low voice. They could not catch the words, but evidently Merry was aroused. His legs began to kick. Tom sprang away, and breaking off a hanging branch smote the side of the willow with it. ‘You let them out again, Old Man Willow!’ he said. ‘What be you a-thinking of? You should not be waking. Eat earth! Dig deep! Drink water! Go to sleep! Bombadil is talking!’ He then seized Merry’s feet and drew him out of the suddenly widening crack.

There was a tearing creak and the other crack split open, and out of it Pippin sprang, as if he had been kicked. Then with a loud snap both cracks closed fast again. A shudder ran through the tree from root to tip, and complete silence fell.

He then encourages the hobbits to follow him to his house and sings and dances his way out of sight. Following as best they can, the hobbits begin to feel the ill will of the forest again: 'They began to feel that all this country was unreal, and that they were stumbling through an ominous dream that led to no awakening' (1.vi.121). But again they are not dreaming, and this time they are able to resist the enchantment of the forest's malice, aided by the murmur of the river that flows downhill past Bombadil's house and the song of Goldberry, daughter of the river (1.vi.121).

Just in case the providential arrival of a powerful figure, who hops and dances instead of walking, and who sings and speaks in verse, were not a clear enough signal that the hobbits were not in the Shire any more, witness their arrival at Bombadil's door:

‘Enter, good guests!’ Goldberry said, and as she spoke they knew that it was her clear voice they had heard singing. They came a few timid steps further into the room, and began to bow low, feeling strangely surprised and awkward, like folk that, knocking at a cottage door to beg for a drink of water, have been answered by a fair young elf-queen clad in living flowers.

(1.vii.123)

As Corey Olsen has rightly

pointed out more than once when speaking of this moment in his podcasts (Mythgard Academy,

The Fellowship of the Ring, class 3, 14:34-25:00), similes usually explain the unusual by comparing it to the usual. Lines of soldiers advancing across a battlefield, for example, are likened to waves approaching a shore, the thickets of their spears to fields of grain. This simile turns that process on its head, and underlines the fact that the hobbits have entered a brave new world that has such people as Tom and Goldberry in it. And Frodo is so inspired by this meeting that he responds to Goldberry's welcome with a song, not in the iambic tetrameter which is characteristic of all the hobbit verse we've seen so far, but in the trochaic rhythms of Tom Bombadil. Even this difference in metrical feet emphasizes the difference between where they've come from and where they are, for iambs and trochees are exact opposites.

‘Fair lady Goldberry!’ said Frodo at last, feeling his heart moved with a joy that he did not understand. He stood as he had at times stood enchanted by fair elven-voices; but the spell that was now laid upon him was different: less keen and lofty was the delight, but deeper and nearer to mortal heart; marvellous and yet not strange. ‘Fair lady Goldberry!’ he said again. ‘Now the joy that was hidden in the songs we heard is made plain to me.

'O slender as a willow-wand! O clearer than clear water!

O reed by the living pool! Fair River-daughter!

O spring-time and summer-time, and spring again after!

O wind on the waterfall, and the leaves’ laughter!’

Suddenly he stopped and stammered, overcome with surprise to hear himself saying such things.

Three times told that they need fear nothing in the house of Tom Bombadil (1.vii.123, 125, 126), the hobbits go to sleep. Three of the four have dreams (1.vii.126-127). Only Sam has none, just as he alone successfully resisted Old Man Willow's spell. Merry and Pippin's dreams are quite ordinary, and reflect their fears, which is hardly surprising given the day they've had. This is all quite different from the enchantment that the hobbits feel in the Forest and in the presence of Bombadil and Goldberry. These are clearly dreams and described as such. The link back to Old Man Willow, and to the remembered (or repeated) advice of Bombadil and Goldberry to heed no nightly noises, underscores the difference between the one form of consciousness and the other.

Frodo's dream here is of course more visionary, as he looks across time and space to observe Gandalf's rescue from the pinnacle of Orthanc by Gwaihir. So Frodo's dream seems an enchanted dream, affected and likely even provoked by the spells that the songs of the Forest, Goldberry, and Bombadil have laid upon him. Neither of his earlier dreams have gone so far beyond the ordinary, though they have hinted at it (1.ii.43; v.108). His next dream will go even farther, as we shall see.

In the morning the experience of enchantment continues. Almost from the moment they wake up, the singing of Tom and Goldberry continues, while outside mist and a 'deep curtain' of rain isolate and insulate the house from the dangers of the forest and black riders (1.vii.128-29). Within, the hobbits have rest and food and freedom from fear. Indeed the only connection to the outside world is the stream that runs downhill past the house, down to the Withywindle, past all the troubles of the forest, and indeed of Middle-earth, to the Sea. And it would seem to be this stream of which Goldberry is singing:

As they looked out of the window there came falling gently as if it was flowing down the rain out of the sky, the clear voice of Goldberry singing up above them. They could hear few words, but it seemed plain to them that the song was a rain-song, as sweet as showers on dry hills, that told the tale of a river from the spring in the highlands to the Sea far below. The hobbits listened with delight; and Frodo was glad in his heart and blessed the kindly weather, because it delayed them from departing.

(1.vii.129)

The story told by Goldberry's song is, moreover, but the prelude to a day of tales from Tom Bombadil, which seem to cover the entire life of Middle-earth, reaching back beyond 'the river and the trees.... before the first raindrop and the first acorn,' even to a time when evil had not yet entered the world (1.vii.131).

The hobbits sat still before him, enchanted; and it seemed as if, under the spell of his words, the wind had gone, and the clouds had dried up, and the day had been withdrawn, and darkness had come from East and West, and all the sky was filled with the light of white stars.

Whether the morning and evening of one day or of many days had passed Frodo could not tell. He did not feel either hungry or tired, only filled with wonder. The stars shone through the window and the silence of the heavens seemed to be round him.

(1.vii.131)

|

| Tom Bombadil © Alan Lee |

This timeless day of rain, song, and story, moreover introduces the most remarkable moment of all. Bombadil puts on the Ring, and it has no effect on him. Nor, when Frodo puts on the Ring, is Bombadil blind to where he is in the room. Clearly Bombadil himself possesses a wider consciousness that perceives more than normal earthly senses can. We've caught a glimpse of this before when Merry and Pippin wake from their dreams in the night and seem 'to hear or remember hearing' the words of both Goldberry and Bombadil to 'heed no nightly noises' (1.vii.127-28). The next morning Bombadil is aware that they awoke in the night without being told (128). Again, the hobbits are clearly not in a place where their normal reality applies, or with people subject to its laws.

Recall also that Bombadil, when asked the night before by Frodo if he had heard him calling and come to help them, denies that he had heard them, and asserts that it was 'chance, if chance you call it' (126), which is reminiscent of Gandalf's suggestion to Frodo that it was more than chance that Bilbo found the Ring (1.ii.55-56), and Gildor's statement to Frodo that '[i]n this meeting [of ours] there may be more than chance' (1.iii.84). There is a larger awareness in all three of these statements that fits in with what we witness with Bombadil and the Ring.

That night, having sat secluded all day behind a 'deep curtain' of 'grey rain' (1.vii.129), and having listened, 'under the spell of Tom's words' (1.vii.132), to tales that included 'strange regions beyond their memory and beyond their waking thought, into times when the world was wider, and the seas flowed straight to the western Shore' (1.vii.131), Frodo seems to dream a dream that again crosses time and space, but this time looks ahead to the moment when his own journey ends:

That night they heard no noises. But either in his dreams or out of them, he could not tell which, Frodo heard a sweet singing running in his mind; a song that seemed to come like a pale light behind a grey rain curtain, and growing stronger to turn the veil all to glass and silver, until at last it was rolled back, and a far green country opened before him under a swift sunrise.

The vision melted into waking; and there was Tom whistling like a tree-full of birds; and the sun was already slanting down the hill and through the open window. Outside everything was green and pale gold.

(1.viii.135)

From the morning of his prophetic dream, which contains elements from his experience and the tales he had heard the day before, and which links back to the dream of the sea Frodo had in Crickhollow immediately before they entered the Old Forest (1.v.108), Frodo wakes into the morning of Tom Bombadil's world. And it is time for the hobbits to begin the journey back to their own. So they go on their way, armed with advice from Tom about the next dangers that lay before them -- the Barrow Downs -- and with a song that will ensure that he will hear them this time if they need help (1.vii.133-34; viii.135-36). As they depart, from a hilltop Goldberry shows them all the surrounding lands, bright and clear in the sunshine, in contrast to the misty world they had seen when they climbed the hill in the Old Forest, a contrast to which the narrator calls our attention (1.viii.135-36). Though they leave her in hope and high spirits, before the day is old things begin to take a darker turn: 'A shadow now lay round the edge of sight, a dark haze above which the upper sky was like a blue cap, hot and heavy' (1.viii.136, emphasis mine).

At noon they climb another hill, from which, as on the hill in the Old Forest, 'the distances had now become all hazy and deceptive' (1.viii.137, emphasis mine). And despite the 'disquiet' they sense from the barrow covered hills that loom over them (1.viii.137), despite the 'warning' of the standing stone that the sun could not warm (137), despite the admonitions of Goldberry to 'make haste while the Sun shines' (1.viii.136), 'they were now hungry and the sun was still at fearless noon; so they set their back against the east side of the stone' (1.viii.137, emphasis mine), just as they had set their backs against Old Man Willow.

Riding over the hills, and eating their fill, the warm sun and the scent of turf, lying a little too long, stretching out their legs and looking at the sky above their noses: these things are, perhaps, enough to explain what happened. However that may be: they woke suddenly and uncomfortably from a sleep they had never meant to take. The standing stone was cold, and it cast a long pale shadow that stretched eastward over them. The sun, a pale and watery yellow, was gleaming through the mist just above the west wall of the hollow in which they lay; north, south, and east, beyond the wall the fog was thick, cold and white. The air was silent, heavy and chill. Their ponies were standing crowded together with their heads down.

(1.viii.137)

Note how the 'perhaps' in the first sentence raises the possibility of a mundane explanation that the 'However that may be' in the next sentence instantly dismisses; and how all the 'nows' and the 'still' in the paragraphs leading up to this moment emphasize the steady encroachment on the hobbits' mind of the barrow wight's 'dreadful spells' (i.viii.140). Their attempt to escape through the fog once they awaken is reminiscent of the moments before they escaped the forest and reached the safety of Tom Bombadil's house, when 'they began to feel that all this country was unreal, and that they were stumbling through an ominous dream that led to no awakening' (i.vi.121). Only this time Tom's house lies behind them and the peril ahead. And what seems like hope and the promise of escape is nearly their undoing:

They were steering, as well as they could guess, for the gate-like opening at the far northward end of the long valley which they had seen in the morning. Once they were through the gap, they had only to keep on in anything like a straight line and they were bound in the end to strike the Road. Their thoughts did not go beyond that, except for a vague hope that perhaps away beyond the Downs there might be no fog.

Their going was very slow. To prevent their getting separated and wandering in different directions they went in file, with Frodo leading. Sam was behind him, and after him came Pippin, and then Merry. The valley seemed to stretch on endlessly. Suddenly Frodo saw a hopeful sign. On either side ahead a darkness began to loom through the mist; and he guessed that they were at last approaching the gap in the hills, the north-gate of the Barrow-downs. If they could pass that, they would be free.

'Come on! Follow me!' he called back over his shoulder, and he hurried forward. But his hope soon changed to bewilderment and alarm. The dark patches grew darker, but they shrank; and suddenly he saw, towering ominous before him and leaning slightly towards one another like the pillars of a headless door, two huge standing stones. He could not remember having seen any sign of these in the valley, when he looked out from the hill in the morning. He had passed between them almost before he was aware: and even as he did so darkness seemed to fall round him. His pony reared and snorted, and he fell off. When he looked back he found that he was alone: the others had not followed him.

'Come on! Follow me!' he called back over his shoulder, and he hurried forward. But his hope soon changed to bewilderment and alarm. The dark patches grew darker, but they shrank; and suddenly he saw, towering ominous before him and leaning slightly towards one another like the pillars of a headless door, two huge standing stones. He could not remember having seen any sign of these in the valley, when he looked out from the hill in the morning. He had passed between them almost before he was aware: and even as he did so darkness seemed to fall round him. His pony reared and snorted, and he fell off. When he looked back he found that he was alone: the others had not followed him.

(1.viii.138-39)

The spells of the Barrow-wight lead the hobbits to a very different door at the top of a very different hill, where Goldberry is not waiting. Unlike under the eaves of the Old Forest, here there is no wholesome enchantment to combat the darkness of the barrow wight's. The song Bombadil had taught them has been for the moment forgotten, whether from their own fear or because they are bewitched.

As we can see, enchanted consciousness can cut both ways, for good or for ill, depending on the source of the enchantment. The whole narrative in this passage, from the moment the hobbits wake up to the moment Frodo is taken by the Barrow-wight, is vague and dark, full of fear and deceptions, the reader having no more idea of what is going on than the characters do (1.viii.140). By contrast, the vivid description of the tales Bombadil tells reads more like the hobbits were witnessing the events rather than just hearing them retold: 'and still on and back Tom went singing out into ancient starlight, when only the Elf-sires were awake' (1.vii.131).

Song has this power in Middle-earth, to fascinate the mind, to shape its perceptions, and even to bring visions of what is being sung; and this has evidently been so since Ilúvatar said 'Behold your choiring and your music' to the Ainur (The Book of Lost Tales 1.55; Silmarillion 17). We have seen this before with Old Man Willow, Bombadil, and Goldberry. We will see it later in Rivendell (2.i.233). We are seeing it now, I would argue, in the perceptions of the hobbits in hours leading up to their capture. Somewhere, as the narrator's dismissal of a more prosaic explanation above, and as Frodo's statement to Merry below, that he 'thought that he was lost' (1.viii.143, emphasis mine), strongly suggest, the Barrow-wight was singing from the moment the hobbits stopped for lunch.

When Frodo awakes in the barrow, a familiar scene greets us. Three hobbits in one state of consciousness, and the fourth in another. Somehow Frodo has sufficiently escaped the enchantment -- perhaps because the Barrow-wight is focussed on the three beneath the sword while casting a further spell upon them -- to take two actions that will combine to save his friends.

Suddenly a song began: a cold murmur, rising and falling. The voice seemed far away and immeasurably dreary, sometimes high in the air and thin, sometimes like a low moan from the ground. Out of the formless stream of sad but horrible sounds, strings of words would now and again shape themselves: grim, hard, cold words, heartless and miserable. The night was railing against the morning of which it was bereaved, and the cold was cursing the warmth for which it hungered. Frodo was chilled to the marrow. After a while the song became clearer, and with dread in his heart he perceived that it had changed into an incantation:

Cold be hand and heart and bone,

and cold be sleep under stone:

never more to wake on stony bed,

never, till the Sun fails and the Moon is dead.

In the black wind the stars shall die

and still on gold here let them lie,

till the dark lord lifts his hand

over dead sea and withered land.

(1.viii.141, emphasis mine)

Faced with this horror, Frodo finds his courage. 'Suddenly' he seizes a sword and slashes off the wight's hand, which seems to free him completely from the spell and gains him the moment he needs:

All at once back into his mind, from which it had disappeared with the first coming of the fog, came the memory of the house down under the Hill, and of Tom singing. He remembered the rhyme that Tom had taught them. In a small desperate voice he began: Ho! Tom Bombadil! and with that name his voice seemed to grow strong: it had a full and lively sound, and the dark chamber echoed as if to drum and trumpet.

Ho! Tom Bombadil, Tom Bombadillo!

By water, wood and hill, by the reed and willow,

By fire, sun and moon, harken now and hear us!

Come, Tom Bombadil, for our need is near us!

There was a sudden deep silence, in which Frodo could hear his heart beating. After a long slow moment he heard plain, but far away, as if it was coming down through the ground or through thick walls, an answering voice singing:

Old Tom Bombadil is a merry fellow,

Bright blue his jacket is, and his boots are yellow.

None has ever caught him yet, for Tom, he is the master:

His songs are stronger songs, and his feet are faster.

There was a loud rumbling sound, as of stones rolling and falling, and suddenly light streamed in, real light, the plain light of day. A low door-like opening appeared at the end of the chamber beyond Frodo's feet; and there was Tom's head (hat, feather, and all) framed against the light of the sun rising red behind him. The light fell upon the floor, and upon the faces of the three hobbits lying beside Frodo. They did not stir, but the sickly hue had left them. They looked now as if they were only very deeply asleep.

(1.viii.141-42, emphasis mine)

As different as the songs of Frodo and the wight are from each other, they are the same in one respect. Both are invocations of a power they do not themselves possess. Despite what we've seen so far, the 'dreadful spells' of the Barrow-wights are limited. The words of the invocation may be 'grim, hard, cold words, heartless and miserable,' but they are also words of deprivation and despair: 'The night was railing against the morning of which it was bereaved, and the cold was cursing the warmth for which it hungered' (1.viii.141). For some kind of redress or revenge, the wight looks to the ending of the world and an unholy resurrection of the dead by the dark lord, whom he cannot or will not name. By contrast, Frodo calls upon Bombadil by name and by all that the wight lacks and hates. A silence falls that is as sudden as the beginning of the wight's song, and Tom's arrival in answer to Frodo's song is as sudden as Frodo's grabbing a sword and striking the wight.

Bombadil's three songs invoke nothing but his own place within the world, and simply issue commands, banishing the wight to the outer darkness (1.viii.142), of which he is just as aware as the wight, and summoning Merry, Pippin, and Sam back from the same long dark (1.viii.143). Tom's power is his own; Tom has no fear; Tom is Master. The wight's invocation goes unanswered. He can no more withstand Tom than Old Man Willow could.

In awakening the hobbits, Tom raises his hand as he sings, which links to the gesture he made when Frodo and Sam rushed desperately at him and the blow he delivered to Old Man Willow (1.vi.119-120), and contrasts the ineffectiveness of wight's invocation of the dark lord who will 'lift his and / over dead sea and withered land' (1.viii.143). Yet, though the wight's final song fails, his earlier spells had no inconsiderable power, putting Merry into a dream in which he re-lived the life and death struggle of one of those originally entombed in the barrow, a dream whose effect intrudes briefly on normal consciousness. This takes the dream consciousness even further in some ways than Frodo's dream of the far green country, since, however briefly, Merry puts on the consciousness of someone else. And this is so potent an experience that he assumes that identity even into the waking world. While Frodo's 'vision melted into waking' (1.viii.135), Merry returns to himself with a bit of a jolt.

But this encounter with the not so dead past effects even Bombadil, who, in breaking forever the spell on the barrow by removing and scattering its treasure, picks out a brooch for Goldberry. He sadly remembers its former owner, and, therefore, clearly knows whose barrow this is: 'Fair was she who long ago wore this on her shoulder. Goldberry shall wear it now, and we will not forget her!' (1.viii.145). Tom draws a further connection to that time by giving the hobbits swords from the mound, 'untouched by time, unrusted, sharp, glittering in the sun,' and tells them something of their history and the Men of Westernesse who forged them (1.viii.146).

And more than that, Bombadil bridges that gap of time for the hobbits, not just in his person and memory, but by conjuring, just as Macbeth's witches do for him (Macbeth 4.1.116-148), a vision of generations of kings:

'Few now remember them,' Tom murmured, 'yet still some go wandering, sons of forgotten kings walking in loneliness, guarding from evil things folk that are heedless.'

The hobbits did not understand his words, but as he spoke they had a vision as it were of a great expanse of years behind them, like a vast shadowy plain over which there strode shapes of Men, tall and grim with bright swords, and last came one with a star on his brow. Then the vision faded, and they were back in the sunlit world. It was time to start again.

(1.viii.146)

And so it was. With Tom as escort, the hobbits make their way fully back to 'the sunlit world.' And just as they had to cross a hedge to leave the Shire, so now they must cross a dike and a line of trees, and pass through the hedge that surrounds Bree (1.viii.146-47; ix.150). 'The shadow of the fear of the Black Riders came suddenly over them again' (1.viii.147, emphasis added) as they come to the border of Tom's land, which 'he will not pass' (1.viii.148). Unbeknownst to the hobbits, moreover, even as they take their leave of Bombadil and approach Bree, the man whom they saw in their shared vision, the man who will wear 'a star on his brow' is 'behind the hedge' listening to their conversation (1.x.163-64; 5.vi.848). This last experience of enchanted consciousness passes the border that Bombadil will not, linking past, present, and future across the boundary between the normal world and Faërie.

Think about it. The hobbits first enter a perilous, enchanted, sentient forest, where 'lived yet, ageing no quicker than the hills, the fathers of the fathers of trees, remembering times when they were lords' (1.vi.130). That is, they remember the times before even the Elves awoke. The hobbits must then cross a haunted land, full of the menace of evil, resentful spirits who inhabit the bodies of the dead, but it is also a land of far more recent origin than the Old Forest, with descendants still wandering the earth, 'sons of forgotten kings,' who, rather than resent what they have lost or what they lack, exercise an anonymous guardianship over others. It is a land pregnant with two possible futures, one of dark resurrection invoked by the barrow-wight, and the other of renewal brought by the man with 'a star upon his brow.'

Precisely between these two lands they find a day of refuge at the house of Tom Bombadil, whose 'country' all this is, not as owner but as 'Master of wood, water, and hill' (1.vii.124, viii.148). Even the Ring seems to have no power here; at least it has none over Tom (1.viii.132-33; cf. 2.ii.265). He is essentially timeless. If the trees were there before the Elves, Tom was there before the trees. If the barrow-wight looks to the return of the Dark Lord (Morgoth, not Sauron), Tom was there before he came the first time. If Tom can remember the most distant night of ancient starlight, he can also foresee the coming of the future king 'with a star on his brow,' and conjure visions of him for others. 'Eldest, that's what I am' (1.vii.131) is perhaps the most accurate and the least cryptic of his statements about himself.

His awareness and memory of all these things across time show that he is not simply the hopping and singing eccentric figure he seems to be, not simply the pre-existing character that Tolkien

just had to fit in somehow, not simply 'the spirit of the (vanishing) Oxford and Berkshire countryside' that Tolkien had invented in

The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, but rather the 'enlarge[d]...portrait' that he suggested to Stanley Unwin (Tolkien,

Letters, no. 19). Far from doing 'little to advance the story,' as

some have held, his role is pivotal in weaving together the various states of consciousness that bind together past, present, and future in

The Lord of the Rings. And his connection to, and unexpected awareness of, people and places beyond his borders -- like Gildor and the Elves, like the Shire and Farmer Maggot, like the Prancing Pony and Barliman Butterbur, like Mordor and the Ringwraiths, and finally like the Dúnedain and Aragorn -- establish the relevance of what goes on within his evidently not impenetrable borders to what goes on outside them.

For most hobbits the lands beyond the Shire are unknown and uninteresting. '[Frodo] looked at maps, and wondered what lay beyond their edges: maps made in the Shire showed mostly white spaces beyond its borders' (1.ii.43). To be sure, Frodo and his companions are hardly ordinary hobbits, but Sam, for example, for all his fascination with old stories of Elves and Dragons, does not even know 'what sort of folk are ... in Bree,' and Merry, though more knowledgeable about the townspeople and the inn, seems never to have been there himself (1.viii.148). Tom's land is the first that they pass through beyond their own. And though they come through the dangers in the Old Forest and the Barrow-Downs unscathed, they do not emerge from his land unchanged.

This journey through Tom's land is so much more than the beginning of a waking dream. It is rather an awakening to a wider world, which does and will require the hobbits to deal with every state from normal consciousness to dream consciousness again and again. These will shape their experiences and be shaped by them until the end of the Tale. They are the beginning of the process of growth that enables them to face the crises with which their errand presents them. It is no accident that in

Homeward Bound Gandalf tells them 'you must settle the [Shire's] affairs yourselves; that is what you have been trained for' directly before he leaves them at the exact place on the road where they had left Bombadil (6.vii.996). Gandalf, moreover, with his task in mortal lands now at an end, crosses over into Tom's land, not to be seen again by the hobbits until they meet him on his way to the Grey Havens.

This moment, when Gandalf has vanished across the Barrow-downs, is also the precise moment at which Frodo remarks to Merry that returning to the Shire feels like falling asleep again. Yet, as we have seen, consciousness is not merely a binary divide between the normal consciousness of waking and the dream consciousness of sleeping. We can easily enough identify three other states:

- Dreamlike Consciousness -- in which the individual seems to himself or another to be dreaming, or in which words such as 'dreamlike,' 'as if in a dream,' 'half in a dream,' etc., would be an apt description.

- Enchanted Consciousness -- in which the individual's perceptions are altered, for good or for ill, by means of enchantment.

- Wider Consciousness -- in which the individual perceives more than what the five senses can communicate.

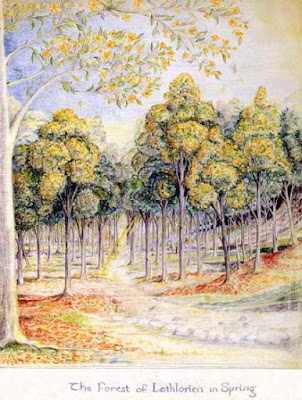

Yet how to arrange these three between the other two is difficult, probably impractical, and most likely irrelevant. The states overlap and blend. Dreams, for example, can be ordinary, like those of Merry and Pippin in Bombadil's house; they can combine with a wider consciousness, like Frodo's that cross time and space; or they can partake of enchanted consciousness as Merry's dream in the barrow seems to do. There is thus no hedge, no river, no line of trees, to mark a clear boundary. The interplay between these states and between the normal world and Faërie argues that these are all, not alternative states or worlds, but integral parts of a greater whole. This greater whole includes Faërie, for the moment, but the references in the passages we have discussed to the seas being bent, to Gandalf's task being done, and to the isolation of Tom's land within Middle-Earth, suggest that Faërie is being increasingly lost. This is in keeping with what we are told elsewhere in The Lord of the Rings of the fading of the Elves, and of the winter of Lothlórien, 'the heart of Elvendom on earth' (2.vi.352), that will nonetheless never see another spring (2.viii.373, 375). Nor it is at all accidental that the prophetic vision Frodo dreams in Tom's house -- of 'a far green country under a swift sunrise' (1.viii.135) -- resumes in the vision he sees in The Mirror of Galadriel of a ship which 'passed away' westward 'into a grey mist' (2.vii.364).

But that is a discussion for another day.

___________________________

Below I have gathered, categorized, and aranged all the references to dreams in The Lord of the Rings. These are passages in which the words dream/dreamed/dreams/dreamless/dreamlike/dreaming and nightmare occur. I have also included passages in which there is no form of the word, but the character is clearly dreaming.

I believe the near absence of recorded dreams after Frodo's 'far green country' dream is significant, but I have not yet sorted out how. I also find it quite interesting that Merry is almost always associated with bad dreams.

Dream Recorded:

FR

1.v.108 (2x -- Frodo at Crickhollow); 1.vii.127: House of TB Frodo (2x), Pippin (3x), Merry (word not used, but he dreams); 1.viii.135 (Frodo, far green country); 2.i.233 (Frodo, enchantment, song, water, 2x), 2.i.237 (Frodo, referring to previous); 2.iii.290 (Frodo).

TT

4.vii.699 (Sam).

RK

none.

Dream Reported/Cited:

FR

1.ii.43; 1.viii.143 (Merry/Carn Dum); 1.x.173 (Merry); 1.xi.177 (Frodo); 1.xii.202 (Frodo); 1.xii.204 (Frodo, half in a dream); 1.xii.211; 2.ii.246 (three times -- Boromir/Faramir); 2.ii.261 (Frodo, referring to 1.vii.127); 2.viii.368;

TT

3.ii.427 (Aragorn); 3.ii.429 (Legolas); 3.ii.434 (Éomer refers to Boromir's dream); 3.ii.442 (Legolas); 3.iii.444 (Pippin, 3 times, "dream-shadows"); 3.iii.448 (Pippin); 3.iii.450 (twice, Pippin and Merry); 3.vi.515 (Théden); 3.vi.516 (Gandalf to Théoden re previous); 4.ii.634 (Frodo, a fair dream, but unremembered); 4.iv.649 (Gollum); 4.iv.655 (Frodo, twice, another fair, unremembered dream); 4.v.671 (twice, Faramir about his/Boromir's dream);

RK

5.i.747 (Pippin); 5.i.748; 5.iii.800 (Merry); 5.vii.852 (twice, Faramir, fevered); 5.viii.858 (twice, Merry, black breath); 5.viii.860 (twice, black breath); 5.viii.863 (black breath); 5.viii.865 (Faramir); 5.viii.868 (twice, Éowyn); 6.i.910 (Frodo, 4 times on page, first and last referring to real dreams); 6.ii.922 (Frodo, dreams of fire); 6.iii.936 (Sam, probably both dream and not dream); 6.iv.951 (first use of three on this page 'and in a dream'); 6.v.962 (the green wave); 6.ix.1024 (Frodo, half in a dream); 6.ix.1030 (Frodo: 'as in the dream in the house of Bombadil').

Dream Metaphor/Simile/Poetry:

FR

1.iii.81, iii.82 (waking); 1.vi.121; 1.vii. 126 (TB); 1.ix.159 (man in the moon); 2.ii.239; 2.iii.272; 2.iii.283; 2.vii.356 (that which haunts our darkest dreams); 2.vii.362; viii.379 (elvish dreams);

TT

3.ii.434; 3.iii.452 (Grishnákh to Uglúk); 3.iii.452 (nightmare); 3.iv.477 (poem: 'dreams of trees'); 3.v.497 (Sauron); 3.viii.547 (Gimli on the Glittering Caves); 3.ix.563; 3.ix.565 (twice); 3.x.580 ('like men startled out of a dream' -- Saruman's voice); 3.x.585; 3.xi.596; 4.ii.627; 4.ii.628; 4.ii.630; 4.ii.632 (nightmare); 4.iii.645 ('as if ... dreaming'); 4.vii.695 (twice); 4.viii.704; 4.ix.725; 4.x.728; 4.x.729; 4.x.734.

RK

5.i.752; 5.ii.788 (?); 5.iii.791 (half-dreaming); 5.viii.871; 5.ix.877; 5.x.886; 6.i.907 (perhaps an allusion to a real dream of Valinor, but more likely metaphorical -- how would anyone know what orcs actually dream?); 6.ii.931 (nightmare); 6.iii.935 ('but the time lay behind them like an ever darkening dream'); 6.vii.997 (Merry and Frodo).

Dream Mistaken/Denied/Dreamless:

FR

1.iii.85; 1.vi.117 (3 times, Old Man Willow); 2.i.219 (Frodo); 2.iv.318 (twice, Frodo, Gollum's eyes, first time clearly not dream, second maybe); 2.vii.358; 2.ix.382 (Sam, Gollum, River, 3 times); 2.ix.383 (Sam, same).

TT

4.v.666 (twice)

RK

5.viii.868 (Éowyn, cf. above dreams reported. 3rd time not a dream -- Théoden); 6.i.910 (Frodo, 4 times on page, 2nd and 3rd not real dreams); 6.iv.951 (Sam, 2nd and 3rd times); 6.ix.1027 (Sam: 'seems like a dream now').

sometime 'half in a dream' seems figurative, sometimes literal