Register for the conference and submit your abstract at IdeasWorthSaving.org

All literature enchants and delights us, recovers us from the 10,000 things that distract us. The unenchanted life is not worth living.

17 December 2024

16 December 2024

Lúthien Unbound?

In his introduction to the Lay of Leithian in The Lays of Beleriand, Christopher Tolkien writes:

My father never explained the name Leithian 'Release from Bondage', and we are left to choose, if we will, among various applications that can be seen in the poem. Nor did he leave any comment on the significance - if there is a significance - of the likeness of Leithian to Leithien 'England'. In the tale of Ælfwine of England the Elvish name of England is Lúthien (which was earlier the name of Ælfwine himself, England being Luthany), but at the first occurrence (only) of this name the word Leithian was pencilled above it (II. 330, note 20). In the 'Sketch of the Mythology' England was still Lúthien (and at that time Thingol's daughter was also Lúthien), but this was emended to Leithien, and this is the form in the 1930 version of 'The Silmarillion'. I cannot say (i) what connection if any there was between the two significances of Lúthien, nor (ii) whether Leithien (once Leithian) 'England' is or was related to Leithian 'Release from Bondage'. The only evidence of an etymological nature that I have found is a hasty note, impossible to date, which refers to the stem leth- 'set free', with leithia 'release', and compares Lay of Leithian.

(Lays 188-89)

Did that last principal part--ἐλύθην/elúthēn--catch your eye? Or maybe your ear? Because it sure caught mine 46 years ago. The Silmarillion had come out a year before and I was reading The Lord of the Rings two or three times a year at that point. So the combination of form and meaning-- a standard translation of ἐλύθην/elúthēn would be "I was set free" or "I was released"--fairly leaped off the page at me. All I could think of was Lúthien and the long poem about her and Beren called The Lay of Leithian and that leithian means "release from bondage."* λύω is the verb you use if you are talking about freeing slaves or prisoners.

I asked my Greek teacher about ἐλύθην/elúthēn after class. Her name was Stephanie and she was probably the best teacher I ever had. She was so good at making things clear, at correcting you without making you feel like an idiot, and she so obviously loved teaching Ancient Greek. I know how she felt. It was later my favorite course to teach as well, but I didn't do it anywhere near as well as she did. In any event in 1978 Tolkien was still largely looked down on in academic circles. As I recall, she said she supposed a connection between this verb and the words Lúthien and leithian was possible, but I could also tell she wasn't really keen on having a prolonged discussion about it.

As we worked our way through the truly immense verbal system of Ancient Greek, we learned more and more forms of this and other verbs. When we came to the form λυθεῖεν, once again my eye was caught because this form can be transliterated in several ways, that is, we can change the word letter by letter from the Greek alphabet into our own. The Greek letter upsilon, |υ|, is commonly represented in English with |y|, as in analysis for the Greek ἀνάλυσις -- and yes, that derives ultimately from the same root. But as the English spelling upsilon attests, |υ| is not always represented by |y|. The diphthong |ει| -- pronounced like |ay| in day in Attic Greek (think Plato) or |ee| in Koine Greek (think the Gospels) -- can be transliterated as |ei| or |i|. So λυθεῖεν could be transliterated lytheien, lythien, lutheien, or luthien. As we can see, Lúthien sounds like it could have its origin here.

How should λυθεῖεν be translated? By form it is the third person plural aorist optative passive. The aorist tense often refers to past time, like a simple past, but not necessarily. It can also refer to something that happens suddenly. So, for example, the form ἐδάκρυσε/edakruse can mean "he wept" but is often better taken as "he burst into tears." And what's the optative? It's like the subjunctive, only more so. It doesn't refer to facts but to possibilities, intentions, hopes, and fears, to things that have not yet become real and may never become real. So λυθεῖεν by itself could be translated as a wish: "May they be set free" or "I wish that they be set free." Which of course would be a very significant name for a character like Lúthien, who comes by this name as Tolkien makes her more powerful and able to release or set free from bondage more things and people. As Clare Moore has shown in her article on Lúthien in Mallorn 62 (2021), with each successive version of her tale, Lúthien's power and importance grow.

Tolkien was keen on the sound of words. He specifically cited Ancient Greek as a tongue that gave him "'phonaesthetic' pleasure" (Letters #144 p. 265).** It may have been hard to resist the combination of sound and meaning to be found in Lúthien.

__________________________________

I hope that the list I've created below helps to clarify the name changes Christopher Tolkien refers to in the quoted passage to start this post. I use > to indicate "becomes" or "changes into"

1. The Tale of Tinúviel in The Book of Lost Tales, vol. II (1917-18)

- The daughter of Thingol and Melian is named Tinúviel, and never called Lúthien.

2. Ælfwine of England in The Book of Lost Tales, vol. II (1917-1918)

- Lúthien = Ælfwine > Ælfwine = Ælfwine

- Luthany*** = England > Lúthien = England ("Leithian" pencilled above 1st use of Lúthien for England)

- The daughter of Thingol and Melian is named Lúthien. Beren, not knowing her name, calls her Tinúviel.

- The daughter of Thingol and Melian is named Lúthien. Beren, not knowing her name, calls her Tinúviel.

4. The Sketch of the Mythology (1926) in The Shaping of Middle-earth.

- Lúthien = Lúthien, daughter of Thingol and Melian

- Lúthien = England > Leithien = England

5. Quenta Noldorinwa (the 1930 Silmarillion) in The Shaping of Middle-earth.

- Lúthien = Lúthien, daughter of Thingol and Melian

- Leithien (Leithian 1x) = England

___________________

*** 'Luthany' seems to come from a poem called "The Mistress of Vision," written by Francis Thompson, a poet of whom Tolkien was quite fond:

The Lady of fair weeping,

At the garden’s core,

Sang a song of sweet and sore

And the after-sleeping;

In the land of Luthany, and the tracts of Elenore.

It's interesting to learn -- thanks to Andrew Higgins's paper, 'O World Invisible We View Thee' The Syncretic Nature of Francis Thompson's Visionary Poems,' which is available here -- that in 1968 George Carter suggested in an unpublished PhD dissertation that Carter suggested that "Thompson constructed 'Luthany' by anglicizing the Ancient Greek aorist passive infinitive of 'luo' – 'luthenai', which means 'to be broken' (Carter 1968, p. 62)."

22 November 2024

The Repentance of Angels: a Curious Departure in Tolkien

“…hoc est hominibus mors, quod angelis casus. Post casum enim non est eis paenitentia, quemadmodum neque hominibus post mortem.”

“…death is to men what the fall is to angels. For after their fall there is no repentance for them, just as there is none for men after death.”

11 October 2024

Prophecy, Hope, Despair, and Sorrow in "The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen."

Recently I have been reading Johm F. Whitmire Jr.'s interesting article, "An Archaeology of Hope and Despair in the Tale of Aragorn and Arwen," in the 2023 issue of Tolkien Studies (vol. XX pp. 59-76). I recommend its thoughtful analysis of the evolution of the Tale over several versions, which are published in The Peoples of Middle-earth (HoMe XII pp. 262-270). The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen is a favorite of mine in any case, and so I enjoyed the opportunity to read it again.

This time through I caught something I had not noticed before. Only six characters play a direct part in the action--others are mentioned--and only these six charactersspeak: Dírhael and Ivorwen, the parents of Gilraen, Aragorn's mother, Elrond, Arwen Undómiel, and Aragorn himself. What I find remarkable is that every one of these six speaking characters displays some degree of accurate prophetic foresight into the fates of the Dúnedain and the heirs of Isildur.

- Dírhael correctly foresees that Arathorn, Aragorn's father, will soon succeed his father, Arador, and perish himself not long after. For these reasons in particular, he opposed the betrothal of Gilraen to Arathorn.

- Ivorwen correctly foresees that Arathorn and Gilraen must marry soon then. "If these two wed now, hope may be born for our people; but if they delay, it will not come while this age lasts.”

- Gilraen gives Aragorn the name Estel (Hope) when his father is killed. Years later she will say that she had given Hope to her people, but kept none for herself.

- Elrond foretells to Aragorn, when he reveals his true name to him, "that the span of your life shall be greater than the measure of Men, unless evil befalls you or you fail at the test. But the test will be hard and long. The Sceptre of Annúminas I withhold, for you have yet to earn it.”

- When Aragorn first meets Arwen and calls her Tinúviel, she says "maybe my doom will be not unlike hers."

- When Gilraen learns that Aragorn has fallen in love with Arwen, she tells him that Elrond will oppose marriage between them. Aragorn replies: "Then bitter will be my days, and I will walk in the wild alone."

- ‘“That will indeed be your fate,” said Gilraen; but though she had in a measure the foresight of her people, she said no more to him of her foreboding, nor did she speak to anyone of what her son had told her.

- Elrond responds as Gilraen predicted and prophesies in turn: “Aragorn, Arathorn’s son, Lord of the Dúnedain, listen to me! A great doom awaits you, either to rise above the height of all your fathers since the days of Elendil, or to fall into darkness with all that is left of your kin. Many years of trial lie before you. You shall neither have wife, nor bind any woman to you in troth, until your time comes and you are found worthy of it.”

- ‘“I see,” said Aragorn, “that I have turned my eyes to a treasure no less dear than the treasure of Thingol that Beren once desired. Such is my fate.” Then suddenly the foresight of his kindred came to him, and he said: “But lo! Master Elrond, the years of your abiding run short at last, and the choice must soon be laid on your children, to part either with you or with Middle-earth.”

- The next time Aragorn sees Arwen many years later: "And thus it was that Arwen first beheld him again after their long parting; and as he came walking towards her under the trees of Caras Galadhon laden with flowers of gold, her choice was made and her doom appointed."

- ‘And Arwen said: “Dark is the Shadow, and yet my heart rejoices; for you, Estel, shall be among the great whose valour will destroy it.” ‘But Aragorn answered: “Alas! I cannot foresee it, and how it may come to pass is hidden from me. Yet with your hope I will hope."

- ‘When Elrond learned the choice of his daughter, he was silent, though his heart was grieved and found the doom long feared none the easier to endure.'

- ‘“My son, years come when hope will fade, and beyond them little is clear to me. And now a shadow lies between us. Maybe, it has been appointed so, that by my loss the kingship of Men may be restored. Therefore, though I love you, I say to you: Arwen Undómiel shall not diminish her life’s grace for less cause. She shall not be the bride of any Man less than the King of both Gondor and Arnor. To me then even our victory can bring only sorrow and parting -but to you hope of joy for a while. Alas, my son! I fear that to Arwen the Doom of Men may seem hard at the ending.”

17 September 2024

The "Real Reason"® Hobbits Don't Like Boats

According to the Prologue to The Lord of the Rings, the sea is a symbol of death to hobbits (FR Pr. 07). We tend to imagine mythical explanations for this perspective. From the Odyssey to Beowulf, the sea has often had associations with death. It's understandable. The sea is vast. It never rests. And it is not your friend. Water always wins. Even in Tolkien's legendarium, west across the sea is the direction the Elves sail off in never to return, and west across the sea lay the great island of Númenor that disappeared beneath the waves long ago. Hearing such stories even remotely, those who knew nothing of the sea, like the hobbits who came to Eriador from beyond the Misty Mountains, couldn't be blamed for thinking the sea was a place to avoid. It might even explain why some of the Stoors turned around and went back over the mountains.

I am here to set the record straight, because the real reason is much simpler than that. The evidence speaks plainly.

- "Indeed, few Hobbits had ever seen or sailed upon the Sea, and fewer still had ever returned to report on it."

- Frodo's parents both fell into the Brandywine River and drowned.

- Even the rumor of this struck terror into the evening crowd at The Ivy Bush.

- After Bilbo's disappearance from the Shire, some insisted that he must have "run off.... and undoubtedly fallen into a pool or a river, and come to a tragic, but hardly an untimely, end."

- Pippin's great great uncle Hildefons "went off on a journey and never returned,"

- Sam leaps into the Anduin to try to catch Frodo before he can paddle away. and he sinks immediately. Frodo has to save him from drowning.

Clearly, Hobbits are negatively buoyant.

They sink like a stone.

______________________________

Dear internet: this is a joke, ok?

Joe Hoffman, this one's for you.

24 August 2024

"Unfey, fearless, and his fate kept him" -- Túrin and Beowulf

The Lay of the Children of Húrin exists in two versions, neither of which tells the whole story its title promises. The second version is much more detailed than the first as far as it goes, but it doesn't go very far. Both versions, however, describe Túrin's earliest days in battle defending the realm of Doriath. The first version offers the following account:

Ere manhood’s measure he met and slew

the Orcs of Angband and evil things

that roamed and ravened on the realm’s borders.

There hard his life, and hurts he got him, 385

the wounds of shaft and warfain sword,

and his prowess was proven and his praise renowned,and beyond his years he was yielded honour;(Lays p. 16, lines 382-88)

The second version is very much the same as the first for the first four and a half lines, but then it rapidly diverges, inserting four and a half entirely new lines before returning to the same conclusion the first version offers:

Ere manhood’s measure he met and he slewOrcs of Angband and evil things 745

that roamed and ravened on the realm’s borders.

There hard his life, and hurts he lacked not,

the wounds of shaft and the wavering sheen

of the sickle scimitars, the swords of Hell,

the bloodfain blades on black anvils 750

in Angband smithied, yet ever he smote

unfey, fearless, and his fate kept him.

Thus his prowess was proven and his praise was noised

and beyond his years he was yielded honour...

(Lays p. 116-17, lines 744-54)

When studying Túrin, it's always a good idea to pay attention to any references to fate. So line 752-- "unfey, fearless, and his fate kept him"-- stuck out, with its two references to fate. "Fey," meaning "doomed to die," is not a word you see every day. "Unfey," meaning "not doomed to die," you see even less. The word has no entry in the OED, and though Google Ngram says it has been used it links to no books in which it is used. According to Google Ngram the word's usage peaked in 1896 -- peaked I say -- at a frequency of 0.0000000216% of all the words in all the books scanned by Google. That's 2.16 times out of every 10,000,000,000 words. For most purposes not requiring a supercollider, this is vanishingly small, quite literally. You need the Webb Telescope to find this thing.

Unless you're reading Tolkien, and you just happen to have been thinking about a line in Beowulf, where Beowulf talks about fighting sea monsters when he was young.

Ac on mergenne, mecum |wunde, 565

be yðlafe uppe lægon,

sweordum aswefede, þæt syðþan na

ymb brontne ford brimliðende

lade ne letton. Leoht eastan com,

beorht beacen Godes, brimu swaþredon, 570

þæt ic sænæssas geseon mihte

windige weallas. Wyrd oft nereð

unfægne eorl, þonne his ellen deah.

But in the morning [the sea monsters] lay dead

on the beach, wounded by my blade,

slain by my sword, so never again

did they hinder the voyages

of seamen on the deep sea.

Light had come in the east, God's bright beacon,

The sea had grown still, so I could see

the headlands and their windy walls.

Fate often keeps an unfey man safe

when his courage avails.

The word unfægne is the masculine accusative singular of unfæge ("unfey"), an adjective which is modifying eorl ("man"), the direct object of the verb nereð ("keeps...safe"). Obviously unfæge derives from fæge ("fey"). Another, related word from elsewhere in Beowulf that should ring a bell is deaðfæge, "doomed to die/death," as in "Nine for mortal men doomed to die." It's important to recognize when reading this line from the Ring-verse that all mortal men are fated to die. That's the whole point, redundant though it may be, of the word "mortal." It is part of their nature. This is true whether we are thinking of fæge, unfæge, or deaðfæge; and this is what makes the escape from death those nine rings seem to promise "the chief bait of Sauron. It leads the small to a Gollum, and the great to a Ringwraith" (Letters #212).

So how can Beowulf speak of a man as unfæge when all men are fæge? As Beowulf himself says when explaining how he survived his fight with Grendel's mother: "Næs ic fæge ða gyt" -- "I was not doomed to die just yet" (line 2146). So fate (wyrd) and courage (ellen) can keep a man safe from dying at the wrong time. On the one hand this tells us that fate is not immutable, and on the other it does not necessarily mean that every man has a specific time to die. A man could be fated to do something he has not done just yet. It's also true that fate and courage do not save always, but merely often.

I find Tolkien's adaptation of Beowulf's words to describe Túrin here particularly interesting because I have been studying the workings of fate in the different versions of The Tale of the Children of Húrin. As I usually do, I am trying to understand this from the ground up, so to speak, looking at how it works in the story and what is said about it, rather than starting with a theory of how fate (doom, destiny, weird, etc) works and applying it to the text.

In Tolkien's prose translation of Beowulf he renders the phrase "Fate oft saveth a man not doomed to die, when his valour fails not" (Beowulf T&C 29). In his commentary on the lines he remarks (Beowulf T&C 256):

To go to the kernel of the matter at once: emotionally and in thought (so far as that was ever clear) this is basically an assertion not only of the worth in itself of the human will (and courage), but also of its practical effect as a possibility, that is, actually a denial of absolute Fate.

15 August 2024

Which hand did Frodo put the Ring on?

A question posted online in a private group set me thinking about which hand Frodo wears the One Ring on. During The Lord of the Rings Frodo puts on the Ring six times: once in the house of Tom Bombadil; once at the Prancing Pony; once at Weathertop; twice on Amon Hen; and once in the Chambers of Fire within Mount Doom. The text mentions which hand he put it on only twice, but it's a different hand each time. That's the curious part.

The first time is on Weathertop:

Not with the hope of escape, or of doing anything, either good or bad: [Frodo] simply felt that he must take the Ring and put it on his finger. He could not speak. He felt Sam looking at him, as if he knew that his master was in some great trouble, but he could not turn towards him. He shut his eyes and struggled for a while; but resistance became unbearable, and at last he slowly drew out the chain, and slipped the Ring on the forefinger of his left hand.

(FR 1.xi.195, emphasis added)

As we know, putting on the Ring reveals him to the Ringwraiths, who attack at once, and the Witch-king wounds Frodo in his left shoulder with a Morgul-knife.

A shrill cry rang out in the night; and he felt a pain like a dart of poisoned ice pierce his left shoulder. Even as he swooned he caught, as through a swirling mist, a glimpse of Strider leaping out of the darkness with a flaming brand of wood in either hand. With a last effort Frodo, dropping his sword, slipped the Ring from his finger and closed his right hand tight upon it.

(1.xi.196, emphasis added).

In Rivendell Frodo is healed of the sorcerous wound to the extent that he can be, but Gandalf, and as we later learn (TT 4.iv.652), Sam, can see the effects.

Gandalf moved his chair to the bedside and took a good look at Frodo. The colour had come back to his face, and his eyes were clear, and fully awake and aware. He was smiling, and there seemed to be little wrong with him. But to the wizard’s eye there was a faint change, just a hint as it were of transparency, about him, and especially about the left hand that lay outside upon the coverlet.

(FR 2.i.223, emphasis added)

Even before Gandalf looks at him, Frodo has checked his left hand to see how it feels (2.i.221). Sam also takes Frodo's hand for the same reason when he enters subsequently (2.i.223). In both of these passages the text again specifies the left hand. The next time we can tell which hand he uses is in the Sammath Naur, but we don't learn it until Sam wakes up in "The Field of Cormallen." Now it is on his right hand (a different finger, too).

He sat up and then he saw that Frodo was lying beside him, and slept peacefully, one hand behind his head, and the other resting upon the coverlet. It was the right hand, and the third finger was missing.

(RK 6.iv.951, emphasis added)

A few other passages are also noteworthy. When Sam puts on the Ring while Frodo is a prisoner, he puts it on his left hand (TT 4.x.734). When Frodo and Sam use the phial of Galadriel against Shelob, each of them holds that in his left hand (4.ix.721, 729). In the case of the phial each already has a sword in his other hand. Consider also this passage from "Mount Doom," ten pages before Frodo claims the Ring and (as we can deduce from which hand is later missing a finger, Watson) puts it on his right hand:

Anxiously Sam had noted how his master’s left hand would often be raised as if to ward off a blow, or to screen his shrinking eyes from a dreadful Eye that sought to look in them. And sometimes his right hand would creep to his breast, clutching, and then slowly, as the will recovered mastery, it would be withdrawn.

(RK 6.iii.935-36, emphasis added)

That Frodo uses his left hand here as if to hide or defend himself, while it's the right hand that's reaching for the Ring, seems quite suggestive. So, although I am not going to speculate about which hand Frodo used the other four times he wore the Ring, or whether his putting it on different fingers on different hands means anything. I will suggest that on balance we may well ask if there's a connection between claiming the Ring and wearing it on the dominant hand, the hand that almost exclusively wields a weapon. For the Ring is a weapon.

--------------------

It may also be worth noting that when Tom Bombadil banishes the wight, he holds up his right hand. Also in Chapter Five of second edition of The Hobbit Bilbo reaches into his pocket and slips the Ring on his left hand (Annotated Hobbit 129, 130, 135). In the first edition Bilbo uses his left hand once (Annotated Hobbit 134). Neither edition mentions his right hand.

14 July 2024

Mani Aroman, Tolkien's Beardless Men

Second, elsewhere but still before the Rohirrim we know appear, Tolkien calls them "Anaxippians" and "Hippanaletians." The first of these clearly derives from Ancient Greek, and means "Horse-Lords" -- anax (ἄναξ) is a good Homeric word for king or lord, and (h)ippos (ἵππος), which we see in both words, means "horse." (Even a decade later he will refer to the Rohirrim as "heroic 'Homeric' horsemen" in Letter 131 (Letters p. 221). "Hippanaletians," aside from its first syllable, is not as easily analyzed, but my best guess so far is that it might mean "wanderers on horseback" -- coined from a combination of ἵππ(ος), ἀν(ά)/on, ἀλήτης/wanderer, hipp-an-aletes. A man who invents entire languages is not going to be shy about coining new words from old languages. "Eucatastrophe" is surely the prime example of this in Tolkien (Letters # 89 p. 142).

"Mani Aroman," however, defied our scrutiny. The words did not seem to be derived from Greek or any other likely language we could think of. Now John Garth had drawn attention to "Mani" and suggested that it might be connected to the names of various ancient Germanic tribes as handed down to us through Latin. For example, the Marcomanni, in which -manni is akin to the English "man," and -marco to "mark." This of course makes the Marcomanni the Men of the Mark, which for obvious reasons is attractive. The "Aroman" didn't fit with this, however.

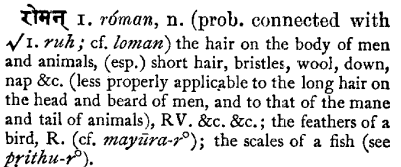

But the "Mani" stuck with me, and eventually I asked myself whether it could be Sanskrit. So I tried some googling and discovered that the Sanskrit word for "man" is "manu:"

I then searched for "Aroman" as a Sanskrit word, and found:

And this is derived from:

11 July 2024

Face up, Face down with Gollum and Boethius

Recently I saw someone somewhere inline asking about Gandalf's characterization of Gollum in The Shadow of the Past.

The most inquisitive and curious-minded of that family was called Sméagol. He was interested in roots and beginnings; he dived into deep pools; he burrowed under trees and growing plants; he tunnelled into green mounds; and he ceased to look up at the hill-tops, or the leaves on trees, or the flowers opening in the air: his head and his eyes were downward.

(FR 1.ii.53)

The poster wanted to know what was so wrong about his not looking up but down. The characterization starts off well enough, but it begins to feel like something has gone wrong when it reaches "and he ceased ... air." And the last phrase, singled out and pointed to by the colon, reads like a final verdict in a capital case. So why is downward bad?

It's part of an old notion that looking up, whether to the heavens or to heaven, is something that distinguishes humans from animals. Off the top of my head I am unsure where it started, but it can be found in Plato and Aristotle. Tolkien was certainly familiar with Plato's Timaeus, which along with the Critias, speaks of Atlantis, and helped inspire Númenor. The description from The Shadow of the Past quoted above makes me think that Tolkien would have more likely been drawing on Boethius' The Consolation of Philosophy, an exceptionally important work in the Middle Ages in Europe. There is even a translation of it into Old English, which has been attributed to Alfred the Great. It probably wasn't really translated by Alfred himself, however, and it's really more of a reboot than a straighforward translation. Tolkien certainly knew both of these works, each of which contains at a similar moment in its fifth book a poem on this difference between humans and animals. First take a look at my translation of a Latin poem from the fifth book of The Consolation of Philosophy. I include the original after that. I've also tried to keep the translation close to the original, line for line, more or less, if not word for word. It's not, however, a literal translation, and I have not tried putting it into verse.

Quam uariis terras animalia permeant figuris!

Namque alia extento sunt corpore pulueremque uerrunt

Continuumque trahunt ui pectoris incitata sulcum,

Sunt quibus alarum leuitas uaga uerberetque uentos

Et liquido longi spatia aetheris enatet uolatu,

Haec pressisse solo uestigia gressibusque gaudent

Vel uirides campos transmittere uel subire siluas.

Quae uariis uideas licet omnia discrepare formis,

Prona tamen facies hebetes ualet ingrauare sensus.

Vnica gens hominum celsum leuat altius cacumen

Atque leuis recto stat corpore despicitque terras.

Haec nisi terrenus male desipis, admonet figura,

Qui recto caelum uultu petis exserisque frontem,

In sublime feras animum quoque, ne grauata pessum

Inferior sidat mens corpore celsius leuato.

inclines to the ground, bends its head down,

Hwæt ðu meaht ongitan, gif his ðe geman lyst,

Þætte mislice manega wuhta

geond eorðan farað ungelice.

Habbað blioh and fær bu ungelice

and mæg-wlitas manega cynna

cuð and uncuð. Creopað and snicað,

eall lichoma eorðan getenge;

nabbað hi æt fiðrum fultum, ne magon hi mid fotum gangan,

Eorð brucan, swa him eaden wæs.

Sume fotum twam foldan peððað,

Sume fierfete, sume fleogende

windað under wolcnum. Bið ðeah wuhta gehwylc

onhnigen to hrusan, hnipað ofdune,

on weoruld wliteð, wilnað to eorðan,

sume nedþearfe, sume neodfræce.

Man ana gæð metodes gesceafta

Mid his andwlitan up on gerihte.

Mid ðy is getacnod þæt his treowa sceal

and his modgeþonc ma up þonne niðer

habban to heofonum, þy læs he his hige wende

niðer swa ðær nyten. Nis þæt gedafenlic

þaet se modsefa monna æniges

19 June 2024

The Politeness of Théoden and the Healing of Gandalf

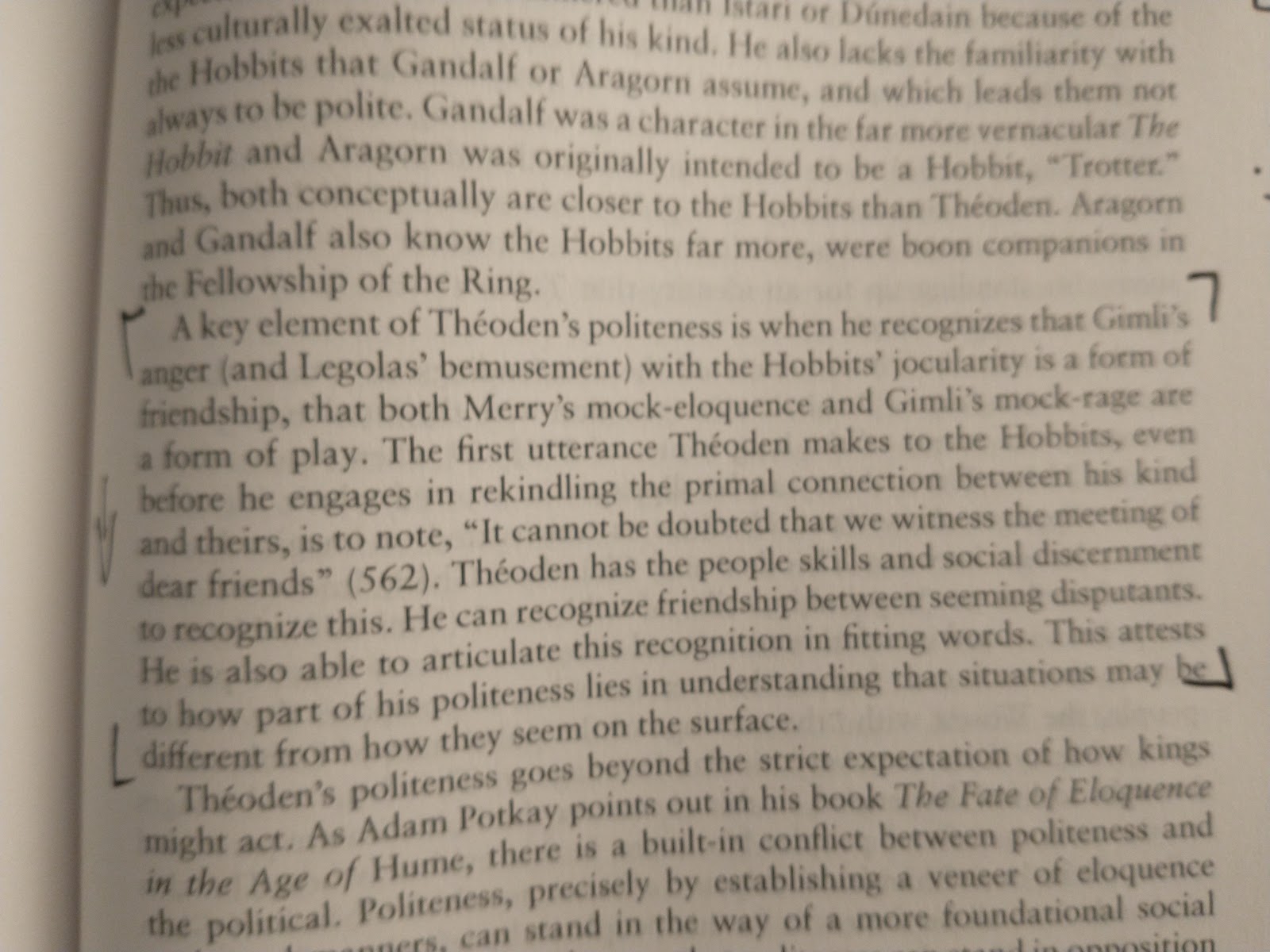

In his new book The Literary Role of History in the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien, Nick Birns has written a very interesting chapter called "Hobbits, the Rohirrim, and Modern Histories of Politeness."

In the paragraph shown below, he comments on what we can see in Théoden's first encounter with Merry and Pippin at the gates of Isengard:

Earlier on Gandalf, Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli had been rather rudely welcomed to Edoras by Théoden and Wormtongue. Gandalf replies as tartly as we might expect him to do: "The courtesy of your hall is somewhat lessened of late, Théoden son of Thengel," (TT 4.vi.513). And even amongst themselves the Rohirrim have seen the politeness appropriate to the King's Hall wear thin. Éomer has threatened Wormtongue with his sword in the hall and disobeyed the King's orders, breaches for which he has been imprisoned.

With this in the background and the King's healing by Gandalf, we can see the politeness of the King which so impressed Merry and Pippin as proof of that healing, and as an assurance that Théoden is restored enough to be able to face Saruman without being taken in by his polite lies. The Riders may doubt him when the moment comes, but Gandalf does not. Nor do most readers, I would imagine.

14 June 2024

"You do not belong here" -- The presence of Men in Faërie

...fairy-stories are not in normal English usage stories about fairies or elves, but stories about Fairy, that is Faërie, the realm or state in which fairies have their being. Faërie contains many things besides elves and fays, and besides dwarfs, witches, trolls, giants, or dragons: it holds the seas, the sun, the moon, the sky; and the earth, and all things that are in it: tree and bird, water and stone, wine and bread, and ourselves, mortal men, when we are enchanted.

On Fairy-stories ⁋ 10, p. 32 (Flieger & Anderson edition)

Reading these words over and over across the years, I have come to conclude that Tolkien did not regard the world as disenchanted, as we often hear it called. To him everything but us was naturally a part of Faërie. We must be enchanted in order to be "contained" in that "realm or state." So, does this mean that we mortals are normally unenchanted, not normally a part of Faërie as everything else in this world is? Or we were once enchanted, but have since become disenchanted by the Fall and expulsion from Paradise, or more mundanely by materialism and positivism and the industrial revolution?

‘But what then shall we think of the union [of fëa and hröa] in Man: of an Indweller [i.e., fëa], who is but a guest here in Arda and not here at home, with a House [i.e., hröa] that is built of the matter of Arda and must therefore (one would suppose) here remain?

(Morgoth's Ring p. 317)

Every other living creature lives and dies with this world, as does every other piece of creation, because this world is "the realm or state in which [they] have their being." In this world, which is coterminous with Faërie, we mortal humans are no more than guests. Faërie is not our home. Or at least it is not the home of our fëa.

As the birch tree in Faërie says to Smith in Smith of Wootton Major: "You do not belong here. Go away and never return!" (Smith, extended edition, p. 30).

20 March 2024

Tolkien Tuesday -- "Pride and Prejudice" -- part 2 (Not All Elves!)

After the composed and often wise Elves we meet in The Lord of the Rings, the dangerously passionate Elves of The Silmarillion can come as quite a shock. I've seen more than one meme contrasting the Elves of the First and Third Ages. When we learn how bigoted many of the Elves were towards Men and Dwarves alike, calling Men "the Sickly" and "the Usurpers" among other charming names, and calling the Dwarves "the stunted people," and hunting them as if they were animals, it can come as something of a disappointment (S 91, 103, 204).

In The Book of Lost Tales we find the earliest evidence for the prejudice against Men, and its roots may be very deep indeed. The first indication comes in "The Music of the Ainur," when Rúmil, the Elf who tells the tale, comments on some of the differences between Elves and Men.

Lo! Even we Eldar have found to our sorrow that Men have a strange power for good or ill and for turning things despite Gods and Fairies to their mood in the world; so that we say: “Fate may not conquer the Children of Men, but yet are they strangely blind, whereas their joy should be great.”

(LT I 59)

Now to be fair to the Elves in The Book of Lost Tales only one group of Men is loyal to the Elves and they pay dearly for it. I mean of course the Men of Hithlum, led by Húrin. His son, Túrin, also sides with the Elves, but his is a complex and troubled legacy. Tuor is also from Hithlum, but unrelated to Húrin at this early stage of the legendarium. Together with his wife, Idhril, he leads the survivors of Gondolin to safety. Their child is Eärendil. (Keep in mind that at this point Beren is an Elf, not a Man.) It's also true that by time Rúmil is telling the tale, thousands of years later, Men and Elves are still in conflict with each other. Blindness may not seem such a terrible thing to accuse them of under the circumstances.

But in The Book of Lost Tales the prejudice of Elves towards Men predates not only their first meeting, but even the awakening of Men. For when the Elves wished to pursue Melkor back to Middle-earth, Manwë tried to dissuade them.

... he told them many things concerning the world and its fashion and the dangers that were already there, and the worse that might soon come to be by reason of Melko’s return. “My heart feels, and my wisdom tells me,” said he, “that no great age of time will now elapse ere those other Children of Ilúvatar, the fathers of the fathers of Men, do come into the world—and behold it is of the unalterable Music of the Ainur that the world come in the end for a great while under the sway of Men; yet whether it shall be for happiness or sorrow Ilúvatar has not revealed, and I would not have strife or fear or anger come ever between the different Children of Ilúvatar, and fain would I for many an age yet leave the world empty of beings who might strive against the new-come Men and do hurt to them ere their clans be grown to strength, while the nations and peoples of the Earth are yet infants.” To this he added many words concerning Men and their nature and the things that would befall them, and the Noldoli were amazed, for they had not heard the Valar speak of Men, save very seldom; and had not then heeded overmuch, deeming these creatures weak and blind and clumsy and beset with death, nor in any ways likely to match the glory of the Eldalië.

LT I 150

That last sentence, which I have italicized, is hardly a flattering portrait of the Elves, and the narrator here in this tale, "The Theft of Melko and the Darkening of Valinor," is another Elf, Lindo. By this time in the story Melkor had been working for some time to estrange the Noldoli (Noldor) from the Valar by insinuating that the Valar had brought the Eldar to Valinor in order to use them as unwitting slaves and to cheat them of their god-given birthright, the world itself. Now Melkor's lies bear fruit, as hearing Manwë about the destiny of Men and the need to give them time to grow, Fëanor puts 2 and 2 together and, quick as an internet conspiracy theorist, comes up with 5.

“Lo, now do we know the reason of our transportation hither as it were cargoes of fair slaves! Now at length are we told to what end we are guarded here, robbed of our heritage in the world, ruling not the wide lands, lest perchance we yield them not to a race unborn. To these foresooth—a sad folk, beset with swift mortality, a race of burrowers in the dark, clumsy of hand, untuned to songs or musics, who shall dully labour at the soil with their rude tools, to these whom still he says are of Ilúvatar would Manwë Súlimo lordling of the Ainur give the world and all the wonders of its land, all its hidden substances—give it to these, that is our inheritance."

(LT I 151)

Of this speech and its consequences, Lindo says:

In sooth it is a matter for great wonder, the subtle cunning of Melko—for in those wild words who shall say that there lurked not a sting of the minutest truth, nor fail to marvel seeing the very words of Melko pouring from Fëanor his foe, who knew not nor remembered whence was the fountain of these thoughts; yet perchance the [?outmost] origin of these sad things was before Melko himself, and such things must be—and the mystery of the jealousy of Elves and Men is an unsolved riddle, one of the sorrows at the world’s dim roots.

(LT I 151)

In this Lindo echoes something he had said previously about the early days of the darkening of Valinor: "Nay, who shall say but that all these deeds, even the seeming needless evil of Melko, were but a portion of the destiny of old?" (LT I 142).

It's easy to see the pride and prejudice of the Elves here, and maybe hear a distant echo of it in Gandalf's remark that the Elves, too, were at fault for their poor relations with the Dwarves (FR 2.iv.303). It's also easy to get the feeling that the sundered paths of Elves and Men begin in the Music itself. What I find most interesting, though, is the way both Manwë and Lindo struggle to understand why things are this way and whether it will prove a good thing in the end. They don't have answers. They have questions and they hope that this evil will be good to have been, even if it remains evil.

19 March 2024

Tolkien Tuesday -- "Pride and Prejudice"

Pride and Prejudice, chapter 1

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.

However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered as the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

Mr. Bennet replied that he had not.

“But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

Mr. Bennet made no answer.

“Do not you want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife, impatiently.

“You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.”

When Mr. Bilbo Baggins of Bag End announced that he would shortly be celebrating his eleventy-first birthday with a party of special magnificence, there was much talk and excitement in Hobbiton.

Bilbo was very rich and very peculiar, and had been the wonder of the Shire for sixty years, ever since his remarkable disappearance and unexpected return. The riches he had brought back from his travels had now become a local legend, and it was popularly believed, whatever the old folk might say, that the Hill at Bag End was full of tunnels stuffed with treasure.

This is probably not what was expected for Tolkien Tuesday, but here it is. There may be more later.

07 March 2024

Forgetting the Way to Faërie -- a bit of L. M. Montgomery and Tolkien

Well, the Story Girl was right. There is such a place as fairyland—but only children can find the way to it. And they do not know that it is fairyland until they have grown so old that they forget the way. One bitter day, when they seek it and cannot find it, they realize what they have lost; and that is the tragedy of life. On that day the gates of Eden are shut behind them and the age of gold is over. Henceforth they must dwell in the common light of common day. Only a few, who remain children at heart, can ever find that fair, lost path again; and blessed are they above mortals. They, and only they, can bring us tidings from that dear country where we once sojourned and from which we must evermore be exiles. The world calls them its singers and poets and artists and story-tellers; but they are just people who have never forgotten the way to fairyland.

The Story Girl -- L. M. Montgomery

I ran across the quote above on the internet the other day, and tracked it down to a 1911 novel by Lucy Maud Montgomery of Anne of Green Gables fame. It interested me for a couple of reasons. First I am trying to gather references to people who visited Faërie as children, but then forgot it and grew up, or grew up and forgot it. Second it reminded me immediately of a passage or two in The Book of Lost Tales, which I've been spending a great deal of time with over the last year. In the following passage an elf is speaking to Eriol, a mortal human mariner who has found his way to Faërie, about mortal human children who had done the same by a different path:

Yet some [human children] there were who, as I have told, heard the Solosimpi piping afar off, or others who straying again beyond the garden caught a sound of the singing of the Telelli on the hill, and even some who reaching Kôr afterwards returned home, and their minds and hearts were full of wonder. Of the misty aftermemories of these, of their broken tales and snatches of song, came many strange legends that delighted Men for long, and still do, it may be; for of such were the poets of the Great Lands.

LT I 19

In this passage Eriol writes in the epilogue of his book:

So fade the Elves and it shall come to be that because of the encompassing waters of this isle and yet more because of their unquenchable love for it that few shall flee, but as men wax there and grow fat and yet more blind ever shall they fade more and grow less; and those of the after days shall scoff, saying Who are the fairies—lies told to the children by women or foolish men—who are these fairies? And some few shall answer: Memories faded dim, a wraith of vanishing loveliness in the trees, a rustle of the grass, a glint of dew, some subtle intonation of the wind; and others yet fewer shall say……

LT II 288

I don't really have much to say about this at the moment, except that the connection between Faërie and poets and memory and forgetting is interesting. I have no information suggesting that Tolkien read Montgomery, though it's not impossible. I thought it might interest others as well.

18 February 2024

Tempt me twice, shame on me -- Sam and the Ring

Over at his blog, Joe Hoffman has thoughtfully suggested that Sam's moment of temptation by the Ring is not in fact his grand vision of being Samwise the Strong, Hero of the Age, who not only defeats Sauron but with a wave of his hand turns Mordor into a garden. Rather, Sam's moment of temptation is his urge to make a heroic last stand defending Frodo from the orcs in the pass of Cirith Ungol.

I must admit I like the idea that this, too, is a temptation produced by the effect of the Ring. But the temptation of the Ring is not simply a one-off event, a test to be passed and left behind. And Sam's love of old stories is also visible in Sam's heroic last stand fantasy "for eyes to see that can" (FR 2.i.223). For when read with Sam's thought of throwing himself upon his sword or leaping from a cliff it shows that the Tale of the Children of Húrin is in Sam's mind in The Choices of Master Samwise (TT 4.x.732).

I can see Sam's temptation beginning in the debate that goes on in his heart and mind about what "see it through" means now that, as Sam believes, Frodo is dead. There is a series of thoughts that runs from revenge (on Gollum) to suicide to duty to heroic sacrifice to the victory garden of Samwise the Strong, that is, from futility to delusion.

_______

I have also come up with a new piece of head-canon and a literary corollary to the laws of thermodynamics.

Reflecting on Sam's vision of turning Mordor into a garden with a wave of his hand, I came to believe that it was the act of forging the Ring that turned Mordor into a dead, poisoned post-industrial wasteland.

Reflecting on Joe's response to what I said in my book and my response to his response, I came to believe that literary interpretations are an expression of the growth of entropy which can only end in the meaning death of the universe.

06 February 2024

Arwen's Green Grave

"... and she went out from the city of Minas Tirith and passed away to the land of Lórien, and dwelt there alone under the fading trees until winter came. Galadriel had passed away and Celeborn also was gone, and the land was silent.

"There at last when the mallorn-leaves were falling, but spring had not yet come, she laid herself to rest upon Cerin Amroth; and there is her green grave, until the world is changed, and all the days of her life are utterly forgotten by men that come after, and elanor and niphredil bloom no more east of the Sea."

(RK App. A, The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen, p. 1063)

Tolkien says that "The Tale of Aragorn and Arwen" is "the highest love story" in The Lord of the Rings (Letters #131 p. 229). He also referred to it as "the most important [tale] of the Appendices; it is part of the essential story, and is only placed so, because it could not be worked into the main narrative without destroying its [hobbit-centered] structure" (Letters #181 p. 343). Since Arwen also makes the Choice of Lúthien, which is the heart of what Tolkien calls "the kernel of the mythology" (Letters #165 p. 320), and The Lord of the Rings is famously part of the story of Beren and Lúthien, it is undeniably a very important tale.

Now sometimes people take the paragraph I quoted at the start to suggest that Arwen despaired at the last, that she lacked the faith Aragorn displayed in his last words: "Behold! We are not bound for ever to the circles of the world, and beyond them is more than memory. Farewell!" In my book, Pity, Power, and Tolkien's Ring: To Rule the Fate of Many, I argued that this was not so (254-58). She is grieving, yes, and full of sorrow, but that is not the same thing as hopelessness. Indeed Aragorn concedes the bitterness of their parting, and that sorrow and grief are a natural part of it. But despair need not be. I am not going to repeat the evidence and arguments I made there, but I would like to add some points here that I think lend additional weight to what I wrote there.

The words that stand out to me as most important are "her green grave" and the most important fact is that her green grave shall endure until the ending of the world and Arda is healed. If we look at an earlier version of these words, which Tolkien abandoned, I think we can notice something else of significance.

Then Arwen departed and dwelt alone and widowed in the fading woods of Lothlórien; and it came to pass for her as Elrond foretold that she would not leave the world until she had lost all for which she made her choice. But at last she laid herself to rest on the hill of Cerin Amroth, and there was her green grave until the shape of the world was changed.

(Peoples 355)

The tone here is quite matter of fact. It's a very prosy account, certainly when compared to the high romantic regster of the passage as published. The draft version records the passing of a world; the published version evokes the sorrow and beauty of its passing. The most significant change, however, is the shift in tense. The original passage simply reports the past. While the published text also begins in the past tense, once Arwen has "laid herself to rest upon Cerin Amroth," that changes. After a brief rest at the semicolon, the sentence begins again with a new movement in the present tense. The combination of the present tenses with the three clauses governed by "until" gives the sentence the vivid prophetic quality that anticipates the future. And the green grave shall be there when that future comes.

Of course her grave's greenness by itself suggests life and growth amid death and the oblivion of time. It's as if the world itself will remember her even if we do not. I did a quick survey of signficant hills and mounds that I could recall. Unsurprisingly, many of those places called "green" are graves, but not all.

But first here's a few hills, which are not graves, and other places where the green seems significant:

- "Before its western gate there was a green mound, Ezellohar, that is named also Corollairë; and Yavanna hallowed it, and she sat there long upon the green grass and sang a song of power, in which was set all her thought of things that grow in the earth" (S 38).

- "To [the Teleri] the Valar had given a land and a dwelling-place. Even among the radiant flowers of the Tree-lit gardens of Valinor they longed still at times to see the stars; and therefore a gap was made in the great walls of the Pelóri, and there in a deep valley that ran down to the sea the Eldar raised a high green hill: Túna it was called. From the west the light of the Trees fell upon it, and its shadow lay ever eastward; and to the east it looked towards the Bay of Elvenhome, and the Lonely Isle, and the Shadowy Seas. Then through the Calacirya, the Pass of Light, the radiance of the Blessed Realm streamed forth, kindling the dark waves to silver and gold, and it touched the Lonely Isle, and its western shore grew green and fair. There bloomed the first flowers that ever were east of the Mountains of Aman' (S 59).

- "Then Tuor looked down upon the fair vale of Tumladen, set as a green jewel amid the encircling hills" (S 239).

- "There came a time near dawn on the eve of spring, and Lúthien danced upon a green hill; and suddenly she began to sing. Keen, heart-piercing was her song as the song of the lark that rises from the gates of night and pours its voice among the dying stars, seeing the sun behind the walls of the world; and the song of Lúthien released the bonds of winter, and the frozen waters spoke, and flowers sprang from the cold earth where her feet had passed" (S 165).

- Cerin Amroth had "... grass as green as Springtime in the Elder Days" (FR 2.vi.350).

- "Three Elf-towers of immemorial age were still to be seen on the Tower Hills beyond the western marches. They shone far off in the moonlight. The tallest was furthest away, standing alone upon a green mound. The Hobbits of the Westfarthing said that one could see the Sea from the top of that tower; but no Hobbit had ever been known to climb it" (FR "Prologue" 7).

- "And the ship went out into the High Sea and passed on into the West, until at last on a night of rain Frodo smelled a sweet fragrance on the air and heard the sound of singing that came over the water. And then it seemed to him that as in his dream in the house of Bombadil, the grey rain-curtain turned all to silver glass and was rolled back, and he beheld white shores and beyond them a far green country under a swift sunrise" (RK 6.ix.1030).

Now here are some graves that are definitely not green, and that's definitely no surprise:

- "the Death Down" under which the orcs slain at Helms Deep had been buried by the Huorns: "no grass would grow there" (TT 3.viii.553).

- "With toil of many hands they gathered wood and piled it high and made a great burning and destroyed the body of the Dragon, until he was but black ash and his bones beaten to dust, and the place of that burning was ever bare and barren thereafter" (Children of Húrin 257).

- "By the command of Morgoth the Orcs with great labour gathered all the bodies of those who had fallen in the great battle, and all their harness and weapons, and piled them in a great mound in the midst of Anfauglith; and it was like a hill that could be seen from afar. Haudh-en-Ndengin the Elves named it, the Hill of Slain, and Haudh-en-Nirnaeth, the Hill of Tears. But grass came there and grew again long and green upon that hill, alone in all the desert that Morgoth made; and no creature of Morgoth trod thereafter upon the earth beneath which the swords of the Eldar and the Edain crumbled into rust" (S 197).

- "‘Yes,’ [Túrin] answered. ‘I fled [the darkness] for many years. And I escaped when you did so. For it was dark when you came, Níniel, but ever since it has been light. And it seems to me that what I long sought in vain has come to me.’ And as he went back to his house in the twilight, he said to himself: ‘Haudh-en-Elleth! From the green mound she came. Is that a sign, and how shall I read it?'" (UT 124; Children of Húrin 218).

- "They buried the body of Felagund upon the hill-top of his own isle, and it was clean again; and the green grave of Finrod Finarfin’s son, fairest of all the princes of the Elves, remained inviolate, until the land was changed and broken, and foundered under destroying seas. But Finrod walks with Finarfin his father beneath the trees in Eldamar" (S 175-76).

- The burial mounds of the kings of Rohan, Théoden's included (TT 3.vi.507; RK 6.vi.976) are all green."Green and long grew the grass on Snowmane’s Howe, but ever black and bare was the ground where the beast was burned" (RK 5.vi.844-45).

- "Then Thorondor bore up Glorfindel’s body out of the abyss, and they buried him in a mound of stones beside the pass; and a green turf came there, and yellow flowers bloomed upon it amid the barrenness of stone, until the world was changed" (S 243).

- Elendil's grave: "...the hallow was found unweathered and unprofaned, ever-green and at peace under the sky, until the Kingdom of Gondor was changed" (UT 309).

Here ends the SILMARILLION. If it has passed from the high and the beautiful to darkness and ruin, that was of old the fate of Arda Marred; and if any change shall come and the Marring be amended, Manwë and Varda may know; but they have not revealed it, and it is not declared in the dooms of Mandos.

(S 255)

The change it mentions is carefully presented in a conditional statement, but the main verb of the "if" clause is "shall," which all but promises that the change will come, and that Marring of Arda will be amended. Think of how differently this would read with even slightly different wording. For "if any change should come," or "will come," or "is to come," or "comes" are all less forceful than that prophetic "shall."

Get out, you old Wight! Vanish in the sunlight!

Shrivel like the cold mist, like the winds go wailing,

Out into the barren lands far beyond the mountains!

Come never here again! Leave your barrow empty!

Lost and forgotten be, darker than the darkness,

Where gates stand for ever shut, till the world is mended.

(FR 1.viii.142)